NELP | WORK SEARCH | NOVEMBER 2023

1

Work Search Requirements

This brief is part of the Unemployment Insurance Policy Hub created by the National

Employment Law Project as a reference guide for state advocates to support efforts that will

strengthen the economic security of workers and their families. For other Policy Hub resources,

see

www.uipolicyhub.org.

Unemployment Insurance (UI) Work Search Definitions

American Jobs Centers (AJCs): Organizations that provide free reemployment services for

unemployed workers. In some states AJCs are integrated into the state employment agency

and in others they operate independently. AJCs operate the Reemployment Services and

Eligibility Assessment program (see below) that plays a part in supporting and monitoring

workers’ work search activities.

1

Improper Payment: A UI payment that an employment agency determines should not have

been made to a recipient.

Reemployment Services and Eligibility Assessment (RESEA): A federal program that

funds state reemployment services for workers deemed likely to exhaust their allotted

weeks of UI benefits before finding work. In some states, RESEA participation is mandatory

for all UI recipients. RESEA participation requires the worker to participate in a meeting

with AJC staff, where they are provided reemployment services and continuing UI eligibility

is assessed.

2

Work Search Exemption: A federal or state law or policy that exempts workers in certain

circumstances from work search requirements. If a worker meets the requirements for an

exemption in any given week, they cannot be deemed ineligible for UI if they do not look for

work in that week.

3

Examples of work search exemptions are discussed below.

Overview

When an unemployed worker files a claim to continue receiving unemployment insurance

(UI) benefits each week, they must certify that they have been actively seeking work. Many

state policymakers have established onerous requirements for documenting work search

activities, which may result in workers’ benefits being cut off without improving their

prospects for finding a good job.

4

Calls for stringent work search requirements tap into age-old racist stereotypes that depict

unemployed workers as lazy and unmotivated to seek work unless they face harsh

POLICY ADVOCACY BRIEF | NOVEMBER 2023

NELP | WORK SEARCH | NOVEMBER 2023

2

penalties.

5

At the same time, strict work search reporting rules create yet another barrier for

workers, including Black workers and other workers of color who already face

disproportionate obstacles to accessing unemployment benefits as a result of structural

racism in the economy.

6

States should act to minimize burdensome work search reporting

requirements and remove unnecessary barriers to accessing UI benefits.

Variation in state work search policies

While federal law requires all states have a work search requirement, states are given a

great deal of latitude in defining it. To be eligible for UI in any given week, workers are

required to actively look for work. Generally, a worker must complete a specified number of

work search activities each week.

Depending on the state, approved work search activities may include actions like creating a

profile on a job-search website, attending trainings on job-search skills like writing cover

letters, participating in job networking events, participating in approved job training,

registering with a staffing service, attending a job interview, or submitting a resume to apply

for jobs.

7

State work search policies vary according to several factors, including:

• The number of weekly work search activities needed to meet the requirement.

• The types of work search activities that meet the requirement (for example, submitting a

resume or participating in job training).

• Whether searching for part-time work meets the requirement.

• When and how a worker must provide proof that they completed required activities.

• The circumstances in which a worker is exempt from the work search requirement.

• The methods the state uses to monitor compliance with work search.

8

States with stringent work search policies

The states with the most stringent work search requirements offer little flexibility,

mandating that workers contact four to five new employers each week and meticulously

report those contacts to the state agency, regardless of whether there are any additional

local employers hiring in their field.

9

Workers in some states must document their work

search activities and make the record available upon request, while others are required to

provide additional proof of their work search activities.

Many of the most stringent requirements were imposed in the years of prolonged high

unemployment during and after the Great Recession, when policymakers in states such as

Florida, Nebraska, and Missouri sought to replenish their UI trust funds by restricting access

to UI benefits rather than raising business taxes. In recent years, states such as Kentucky and

Arkansas have increased work search requirements. Increased work search documentation

requirements and ramped up enforcement of work search were among the means of

reducing access.

10

The greater focus on work search succeeded in increasing denials of UI benefits and

reducing overall UI recipiency. From 2007 to 2011, approximately 4 out of every 100 weekly

claims filed nationally resulted in workers being disqualified for UI benefits because they

were determined not to meet the requirements of being able to work, being available for

work, or actively searching for work. Between 2012 and 2016, the national rate jumped to 7

NELP | WORK SEARCH | NOVEMBER 2023

3

in every 100 of workers being disqualified for UI benefits. In the 10 states with the most

stringent work search requirements, more than 15 of every 100 unemployment claims were

denied because workers could not meet new documentation requirements that demanded

they repeatedly prove they were able, available, and actively seeking work.

11

States that minimize work search barriers

In contrast, states that are committed to facilitating access to UI benefits for jobless workers

minimize the barriers posed by work search reporting by:

• Allowing a broad range of work search activities to count toward the requirement.

• Requiring a worker to report only minimum activities each week (e.g., one or two

activities).

• Having an expansive list of circumstances where work search is not required.

• Requiring workers to attest to work search compliance but only prove their work search

when requested.

• Monitoring compliance through USDOL’s Benefit Accuracy Measures audit process only

(see below for details on this process).

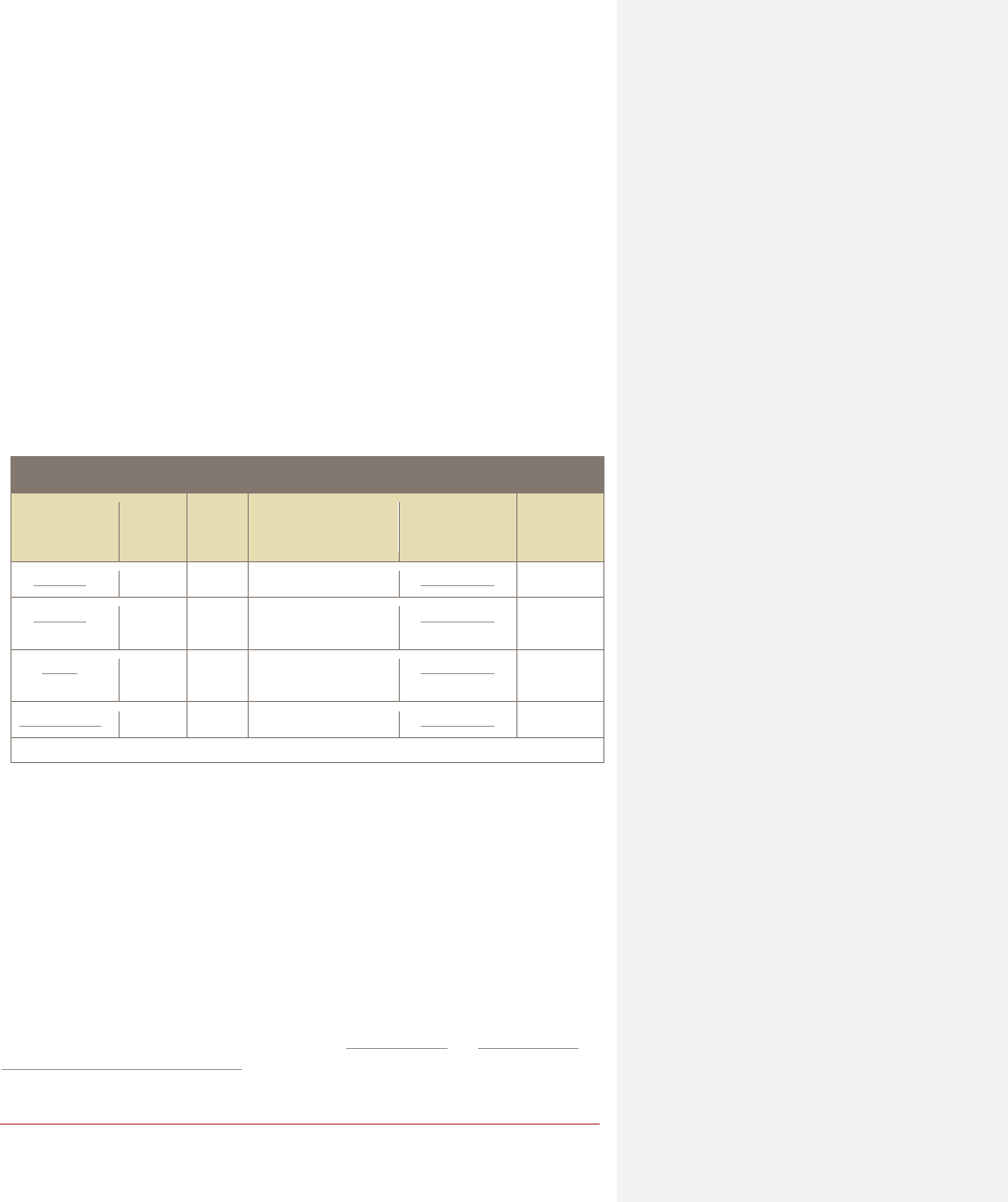

Table 1. Example States that minimize work search barriers

State

Min.

activities

required

Part-

time

allowed

Reporting required

Types of activities

that count

Broad work

search

exemptions

California

12

1

Yes

Upon request

Expanded list

Yes

Delaware

13

1

Yes

Work search log

required upon request

Expanded list

Maine

14

1

Yes

Work search log

required upon request

Expanded list

Massachusetts

15

3

Yes

Upon request

Expanded list

Yes

Source: USDOL Comparison of State Unemployment Laws (2021).

Another approach to minimizing work search barriers is found in the Michigan work search

law.

16

In Michigan, the state agency can pause mandatory work search reporting when the

agency determines that state or local labor market conditions warrant it. As a result,

Michigan effectively turns off its work search requirement when the statewide

unemployment rate is 8.5 percent or above.

17

USDOL measures state work search compliance

USDOL measures state work search compliance through an internal audit program called the

Benefit Accuracy Measurement (BAM) program. BAM uses a small sample (fewer than 500

claims per year, depending on the size of the state) of randomly selected actual claims to test

for improper payments. As a part of a BAM audit, staff review the claim to determine

whether the worker has met the work search requirement. The agency may contact the

worker for proof. For additional details, see USDOL’s

BAM Fact Sheet and Unemployment

Insurance Performance Management site.

NELP | WORK SEARCH | NOVEMBER 2023

4

Work search requirements during the pandemic

Congress gave states temporary flexibility to modify or suspend work search requirements

in March 2020 in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. This emergency flexibility lasted until

September 6, 2021. Most states made at least some changes to their work search

requirements during the pandemic, with many completely suspending them.

18

Removing

pointless work search requirements allowed more workers to access benefits during the

economic crisis.

Federal Requirements and Guidance

Federal law requires a worker to be “actively seeking work” to remain eligible for UI.

19

In

part because all states had work search requirements prior to the federal adoption, states

have significant flexibility in defining what constitutes “actively seeking work.”

USDOL has said state law definitions need only be (1) “reasonable” and (2) ensure that

workers “will be engaged in concerted and effective efforts calculated to find a suitable job in

the shortest period of time that is practicable.”

20

In other words, state requirements around

the type or number of work search activities “must be closely tie[d] to an expectation that

the worker will be quickly reemployed.”

21

See UIPL 5-13 for USDOL guidance on the federal

work search requirement.

Federal law allows for two explicit exemptions to the work search requirement for workers

participating in: (1) state-approved training

22

or (2) a Short-Time Compensation program

23

(see the USDOL Short-Time Compensation website for more information about this

program). State laws also allow for some exemptions to mandatory work search, such as in

times of high unemployment. Other examples of exemptions include when a worker:

• Has been temporary laid off with a definite return date.

• Has a specified start date with a new employer.

• Is in a union that finds work through a union hall.

• Is on jury duty.

24

A brief overview of the federal work search requirement and how each state has

implemented the requirement is available in USDOL’s

Comparison of State UI Laws.

Practice note: States are not required to have their work search policy in statute to comply

with the federal requirement. Work search rules contained in state regulation, agency policy,

or even case law can satisfy federal conformity requirements. See Table 5-14 in the

2021

Comparison of State UI Laws for a breakdown of the basis for work search requirements in

each state. This means that state work search reform is not necessarily limited to legislative

change. Policy improvements can be instigated by state regulation, agency policy, or even

case law.

Policy Recommendations

States should ensure that workers do not have to jump through unnecessary bureaucratic

hoops to retain access to UI benefits. To minimize the barriers posed by work search

reporting requirements, states should:

1. Exempt certain categories of workers from work search requirements.

Commented [AT1]: Updated link

NELP | WORK SEARCH | NOVEMBER 2023

5

Over the years, states have recognized that work search reporting requirements are not

reasonable for certain categories of workers. States should exempt workers in the

following circumstances from mandatory work search reporting:

• Workers on temporary layoffs. Many states provide a work search exemption for

workers who are temporarily laid off. When setting up the exemptions, states should

broadly define what qualifies as a “temporary layoff,” and the duration of the

exemption should last for the entire length of the claim. Because planned return-to-

work dates tend to change and communication from employers can be confusing, the

exemption should not be tied to a fixed number of days or a determination made by

the employer at the time of the layoff.

The method for obtaining an exemption for a temporary layoff is also important. As

much as possible the exemption should be automatic when the worker (not the

employer) certifies that they meet the required set of circumstances.

In many states, an employer applies for a work search waiver on behalf of the worker.

Employers who put their workers on temporary or seasonal layoffs do this because

they want their skilled workers to return to their business when the temporary layoff

is over. However, not all employers who place workers on temporary layoff apply for a

work search waiver for their employees, even though the worker is entitled to a

waiver.

To address the situation of employer neglect, workers must be allowed to claim the

work search waivers themselves by self-certifying that they meet the criteria for a

temporary layoff. The employer could contest the work search exemption if

warranted. Another solution is to require employer-filed claims for all temporary

layoffs. This then could trigger automatic work search exemptions for workers. For

example, Georgia required employer-filed claims during the pandemic, and it eased

the claim processing burden on the system and dramatically sped up claim payment.

25

• Workers in approved job training. One federally mandated exemption is approved

job training.

26

Work search exemptions for workers in approved training should

include participation in agency-approved trainings or trainings approved by the Trade

Adjustment Act. State workforce agencies should expand the types of trainings they

approve and make the approval request process well-known and easily accessible.

• Workers participating in the Short-Time Compensation program. Another

federally mandated exemption is for workers participating in a Short-Time

Compensation layoff.

27

See the USDOL Short-Time Compensation website for more

information about this voluntary state program that gives employers an alternative to

layoffs when they need to reduce worker hours temporarily.

• Workers on jury duty. Workers on active jury duty in any given week should not be

required to report work search activities during that week.

• Workers in labor markets experiencing high unemployment. Recognizing that it

is harder to find a job when unemployment is high, some states have a work search

exemption that is indexed to the statewide unemployment rate.

NELP | WORK SEARCH | NOVEMBER 2023

6

For example, in Michigan when the unemployment rate reaches 8.5 percent or higher,

it is presumed that suitable work is not available and the work search reporting

requirement is waived.

28

States can improve on Michigan’s model by implementing a

work search waiver based on regional or local unemployment rates. This is because a

statewide work search trigger does not account for higher-than-average

unemployment rates in different regions of the state.

• Workers currently working part-time. To encourage workers who are seeking full-

time work to accept part-time employment while claiming partial UI, workers

receiving partial benefits should not be subject to work search reporting

requirements. Studies show that workers who work part-time while claiming benefits

are more likely to return to full-time work and to do so more quickly than those who

do not work.

29

2. Reduce the number and reform the type of work search activities that

fulfill requirements.

• Allow search for part-time work to satisfy requirements. To keep pace with the

modern economy that includes many part-time jobs, searching for part-time work

should satisfy the mandatory work search requirement. Allowing a search for part-

time work is particularly important for women, who still disproportionately shoulder

caregiving responsibilities, and for people with disabilities, who may be unable to

work full-time due to health conditions. Both women and people with disabilities are

more likely to seek part-time jobs.

30

As of 2021 there were 33 states that allowed

workers to only search for part-time work under a large range of circumstances.

31

• Limit the number of weekly search activities required. To minimize bureaucratic

hurdles, states should require workers to report only one or two work search

activities each week. Where possible this number should be codified in statute to

prevent overzealous state workforce agencies from implementing more onerous

requirements. Approximately one-third of states—including states like Montana,

Oklahoma, and Wyoming—only require one or two work search activities per week,

and they still have solvent trust funds, low unemployment rates, and relatively low

benefit exhaustion rates.

32

• Allow workers flexibility in how they conduct their work search. Most workers

front-load their work search activity (for example, learning job-search skills, making a

resume, creating a profile on job websites, and sending applications to an initial round

of employers) in the early weeks of their unemployment rather than doing the same

number of work search activities each week. Workers should be allowed to count all

their work search activity in any week it is conducted to meet the requirement.

• Expand the types of activities that satisfy requirements. Beyond simply submitting

a job application, workers should be able to fulfill work search requirements with

other activities that are conducive to finding employment in today’s job market. These

could include:

▪ Using reemployment services at an American Jobs Center (AJC).

NELP | WORK SEARCH | NOVEMBER 2023

7

▪ Creating a user profile on a professional networking site.

▪ Registering for work with a private employment agency.

▪ Attending a job-search seminar.

▪ Sitting for a state civil service exam.

California, Massachusetts, New York, and Michigan are examples of states that

recently expanded the types of acceptable work search activities.

3. Reform work search monitoring and reporting requirements. States have

considerable latitude in how they monitor workers’ compliance with work search

requirements and in when they require a worker to submit proof of work search. States

should use this flexibility to ease the burden of mandatory work search.

• Monitor work search compliance through BAM review or random audits.

States should verify work search by relying on USDOL’s BAM review process, as

described above, or through random audits instead of by requiring workers to submit

extensive weekly or bi-weekly documentation.

Currently all states ask workers on their weekly certifications to attest that they are

able to, available for, and actively seeking work. Some states have also begun

requiring that workers submit proof of their work search at the time of their weekly

certifications. This weekly reporting of work search activity is not required by USDOL

and can result in more denials of UI benefits and lower recipiency rates.

33

States

should simply advise workers to keep track of their work search activity to make it

available upon request, which 20 states—including Wyoming, Texas, and Kentucky—

already do.

34

• Allow individual “good cause” exceptions if workers are unable to meet work

search requirements. Workers should not become ineligible for UI benefits if they

have good cause for being unable to conduct work search activities. Good cause should

include being unable to fulfill work search requirements because of circumstances

beyond the worker’s control, such as an employer’s promise to recall laid off workers

that does not materialize, language access issues, or an inability to access

transportation to attend a planned work search activity.

• Ensure workers who fail to meet a work search requirement are only ineligible

for that week. Typically, when workers are determined ineligible for UI benefits

because of failing to comply with the requirement that they be “able and available” to

work, the ineligibility lasts indefinitely. The worker is ineligible until they prove they

are able or available for work.

Some states apply this same standard to work search and disqualify a worker

indefinitely until the worker proves they are/were looking for work in subsequent

weeks. Unlike the “able and available” standard, failing to report work search activity

in one week is not evidence that a worker did not search for work in subsequent

weeks. For that reason, states should only disqualify workers for the week they did

not meet the work search requirement and not indefinitely.

• Enable workers to easily report activity with job-finding services. In states that

insist on weekly or bi-weekly reporting of proof of work search activities, workers

NELP | WORK SEARCH | NOVEMBER 2023

8

should be allowed to easily document their online activity with job-finding services

such as LinkedIn, Monster, RESEA, and AJCs.

Prior to the pandemic, LinkedIn began a push to create a bridge between their job-

finding service and state agency portals to allow easier worker reporting of work

search. States with a weekly work search reporting requirement should explore how a

worker could forward activity on job-finding sites to state agencies to prove

compliance.

4. Improve worker communication and due process. Use meaningful reminders to

promote work search compliance and improve work search forms and communications.

States should use proactive and supportive methods and clear and timely

communications to assist workers in complying with mandatory work search reporting.

As part of an effort led by the National Association of State Workforce Agencies, some

states are exploring using better communication and lessons from behavioral science to

improve work search compliance. Recommended improvements include using

automated text messages to remind workers to report work search activity and

providing links to work search reporting forms.

35

Research Findings and Arguments to Support Reform

Burdensome work search requirements do not help workers find jobs.

Research on the effectiveness of work search requirements shows mixed results. While

many studies find that imposing work search requirements reduces the length of time that

workers receive UI benefits,

36

workers may simply have their benefits terminated without

finding work or be obliged to accept work that is a poor match for their skills and

experience.

One study in Maryland found that when the state eliminated its requirement that workers

contact a certain number of employers, workers’ post-UI earnings increased, suggesting that

delayed exit from UI improved job matches.

37

Another study looking at multiple states found

no evidence that verifying work search activities leads to shorter claims or lower benefit

payments.

38

No research has found that requiring workers to contact five or more employers

per week—as the most stringent states now require—offers any benefit to workers in terms

of employment or wages. On the other hand, voluntary job-matching assistance and other

supports do lead to better outcomes for workers.

39

Stricter work search requirements lead to fewer unemployed workers

receiving UI benefits.

In recent years, policymakers in states such as Florida, Nebraska, and Missouri increased

work search documentation requirements and ramped up enforcement of work search,

contributing to a decline in the percentage of unemployed workers who received UI

benefits.

40

As more workers are denied benefits for falling short of work search documentation

requirements, UI recipiency rates are falling. Nationally, the percentage of unemployed

workers receiving benefits was around 23 percent prior to the COVID-19 pandemic.

41

Work search requirements are rooted in racist stereotypes.

NELP | WORK SEARCH | NOVEMBER 2023

9

White supremacy is founded on pernicious myths depicting Black people as lazy and

indolent that were used to justify slavery and later to continue controlling Black lives and

labor.

42

Contemporary work search requirements tap into these racist stereotypes: although

the majority of unemployed workers are white, conservatives mobilize racial bias to depict

unemployed workers as undeserving people of color who do not want to work, are seeking

to game the system, and must be coerced by law to find employment.

43

These covert racist appeals were evident in the Congressional debate when work search

requirements were codified as part of federal law. When the Middle Class Tax Relief and Job

Creation Act passed in early 2012, there were four unemployed workers for each available

job opening,

44

yet the work search requirement implied that workers’ inability to find

employment stemmed from personal failure to search diligently for jobs. “There should be

an incentive all the way through this process to get people to really do the job of getting out

there and looking for work,” explained supporter Representative Charles Boustany of

Louisiana.

45

The debate on the legislation featured lurid stories of “convicted murderer Anthony Garcia

[who] continued to collect $30,000 in unemployment benefits . . . while he served time in the

LA County jail system.”

46

Deploying negative stereotypes of convicted people, Latinx

workers, and unemployed workers, legislation became law that mandated work

requirements and allowed states to conduct invasive drug tests on workers applying for UI

benefits.

Work search reporting rules are another barrier to access for workers of

color.

The UI system is structured in ways that disproportionately shut out Black workers and

other workers of color, particularly women of color. For example, because of structural

racism and sexism in the labor market, women of color disproportionately work in low-

paying positions with fluctuating schedules. As a result, they are more likely to be excluded

by UI eligibility rules that mandate a certain minimum income or hours worked.

47

In addition, Black and Latinx households are more likely than white households to rely on

smartphones to access the internet, making it more difficult to report work search activities

on state unemployment websites that are not optimized for mobile devices.

48

While there is

little data available to examine how work search rules specifically impact workers of color,

reporting requirements are an additional hurdle for workers who already face greater

obstacles to accessing UI benefits.

Stringent work search requirements create needless administrative costs.

Work search monitoring is expensive for state agencies and does not save money for UI

programs in the long run.

49

Most state agencies are not able to automate the review of work

search forms and do not have the staff resources to complete an individual review of each

weekly work search form. For both efficiency and good policy reasons, most states (35)

monitor work search compliance through random audits of individual claims. Better yet,

seven states rely simply on the BAM review for compliance monitoring.

50

States with flexible work search monitoring are better able to meet USDOL

performance standards.

NELP | WORK SEARCH | NOVEMBER 2023

10

States with less onerous work search requirements and more flexible monitoring schemes

are better able to meet federal improper payment standards. When work search was made a

federal requirement, USDOL created performance standards for work search-related

improper payments.

51

Since then, USDOL identified failure to comply with work search

requirements as a leading cause of improper payments.

52

States with high improper

payment rates have been placed on corrective action plans and are looking for ways to

reduce improper payments. One way to reduce improper payments is to use less onerous

work search requirements.

Data and State Comparison Resources

Compare your state’s UI work search requirements to other states.

Consult USDOL’s annual

Comparison of State Unemployment Insurance Laws for comparisons

of states’ work search rules, including:

• The minimum number of work search activities required per week, whether searching for

part-time work is acceptable, and the basis for work search requirements in state law,

regulation, or policy (Table 5-14).

• The frequency and methods for reporting work search activities and the types of work

search reviews states conduct (Table 5-15).

This resource is updated annually, so table references may change.

Find data on the number and proportion of workers denied UI benefits in your

state because they were not “able, available, and actively seeking work” (a

category that includes work search denials).

The Century Foundation’s

Unemployment Insurance Data Explorer provides updated

unemployment data from USDOL in graphs. Advocates can select their state from a drop-

down menu, choose a timeframe, and look at “non-separation denial breakdown” rates by

quarter. Workers who are denied UI benefits because they did not meet work search

requirements are included in the “able and available” category. To download a spreadsheet

with numbers of workers denied UI in your state, click the “download data” button

underneath the chart and look at the column for “Non-Monetary Able & Available Denials.”

This website also offers resources for comparing states.

This data is also available directly from USDOL via its

ETA 207 - Nonmonetary

Determinations Activities Report, but the Century Foundation website is more user-friendly.

Find the percentage of unemployed workers that receive UI in your state and

compare to other states.

Overly restrictive work search requirements are one reason why so many unemployed

workers are denied UI benefits. Check the Century Foundation’s Unemployment Insurance

Dashboard and click on “How many are getting UI” and “Recipiency Rate” to see the

percentage of all unemployed workers receiving UI benefits by state.

Find data on claims flagged by USDOL for not meeting work search

requirements.

USDOL tracks what are considered improper payments to workers who do not meet state

work search requirements as part of the state’s BAM. Note that being flagged by BAM does

NELP | WORK SEARCH | NOVEMBER 2023

11

not necessarily mean a claim was denied by the state. National and state BAM data is

reported on USDOL’s Unemployment Insurance Performance Management page.

Note that USDOL warns against making state-to-state comparisons on improper payments

connected to work search requirements: “As a result of diverse work search eligibility

requirements and enforcement standards, there is tremendous variability in work search

error rates among states. A lower error rate could reflect a higher rate of work search

compliance within the state, which in turn could be due either to greater search efforts by

workers or to less stringent requirements for work search. Other variables include the

circumstances such as where the [State Workforce Agency] considers workers’ lack of

compliance in work search or reporting as constituting an improper payment; or varying

[State Workforce Agency] standards for verification of worker provided contacts/activities.

UI program structural issues also contribute to a higher work search improper payment

rate.”

53

References and Essential Articles

Overview of work search requirements

Josh Bivens et al., Reforming Unemployment Insurance, Center for American Progress, Center

for Popular Democracy, Economic Policy Institute, Groundwork Collaborative, National

Employment Law Project, National Women’s Law Center, and Washington Center for

Equitable Growth, June 2021, starting at 57,

https://s27147.pcdn.co/wp-

content/uploads/Reforming-Unemployment-Insurance-June-2021.pdf.

George Wentworth, Closing Doors on the Unemployed, National Employment Law Project,

December 19, 2017,

https://www.nelp.org/publication/closing-doors-on-the-unemployed/.

Work search and racial inequity

Moneé Fields-White et al. Unpacking Inequities in Unemployment Insurance, New America,

September 17, 2020, https://www.newamerica.org/pit/reports/unpacking-inequities-

unemployment-insurance/.

Elisa Minhoff, The Racist Roots of Work Requirements, Center for the Study of Social Policy,

February 2020,

https://cssp.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Racist-Roots-of-Work-

Requirements-CSSP-1.pdf

Academic studies on the impact of work search requirements

Daniel H. Klepinger et al., “Effects of Unemployment Insurance Worksearch Requirements:

The Maryland Experiment,” Industrial and Labor Relations Review 56, no. 1 (October 2002):

3–22, http://pinguet.free.fr/klepinger2002.pdf.

Duncan McVicar, The Impact of Monitoring and Sanctioning on Unemployment Exit And Job-

Finding Rates, IZA World of Labor, June 2020,

https://wol.iza.org/uploads/articles/540/pdfs/impact-of-monitoring-and-sanctioning-on-

unemployment-exit-and-job-finding-rates.pdf.

Marios Michaelides et al., Impact of the Reemployment and Eligibility Assessment (REA)

Initiative in Nevada, IMPAQ International, LLC, January 2012,

https://wdr.doleta.gov/research/FullText_Documents/ETAOP_2012_08_REA_Nevada_Follo

w_up_Report.pdf.

Commented [AT2]: Updated link

NELP | WORK SEARCH | NOVEMBER 2023

12

Endnotes

1

See USDOL’s Employment and Training Administration’s American Jobs Center landing page,

https://www.dol.gov/agencies/eta/american-job-centers.

2

See USDOL’s Employment and Training Administration’s Reemployment Services and Eligibility Assessment Grants landing page,

https://www.dol.gov/agencies/eta/american-job-centers/RESEA

3

See “Comparison of State UI Laws, Chapter 5, Nonmonetary Eligibility”, US Department of Labor, 2021, 5-30,

https://oui.doleta.gov/unemploy/pdf/uilawcompar/2021/nonmonetary.pdf.

4

George Wentworth, “Closing Doors on the Unemployed,” National Employment Law Project, December 19, 2017,

https://www.nelp.org/publication/closing-doors-on-the-unemployed/.

5

Elisa Minhoff, “The Racist Roots of Work Requirements,” Center for the Study of Social Policy, February 2020, https://cssp.org/wp-

content/uploads/2020/02/Racist-Roots-of-Work-Requirements-CSSP-1.pdf

6

Amy Traub and Kim Diehl, “Reforming Unemployment Insurance is a Racial Justice Imperative,” National Employment Law Project,

February 28, 2022,

https://www.nelp.org/publication/reforming-unemployment-insurance-is-a-racial-justice-imperative/.

7

These examples come from California’s Employment Development Department. See “Job Seekers: Returning to Work,” State of

California Employment Development Department,

https://edd.ca.gov/en/Unemployment/return-to-work.

8

All states monitor work search compliance through the Benefits Accuracy Measurement program and Reemployment Services and

Eligibility Assessment program appointments when required of workers.

9

Wentworth, “Closing Doors on the Unemployed.”

10

Id.

11

The 10 states with the highest rates of disqualification for able, available, and work search issues between 2021 and 2016 were

AK, FL, ID, MO, OH, NE, NH, ND, SC, and UT.

Wentworth, “Closing Doors on the Unemployed.”

12

“Job Seekers: Returning to Work.”

13

“Work Search Frequently Asked Questions,” Delaware Department of Labor, Division of Unemployment Insurance,

https://labor.delaware.gov/divisions/unemployment-insurance/unemployment-benefits-faqs/works-search-frequently-asked-

questions/.

14

“Work Search Requirement,” State of Maine Department of Labor, Unemployment Insurance,

https://www.maine.gov/unemployment/faq/worksearch/.

15

“Work search examples,” Massachusetts Department of Unemployment Assistance, https://www.mass.gov/service-details/work-

search-examples.

16

See “Michigan Employment Security Act,” Mich. Comp. Laws Ann. §421.28, http://legislature.mi.gov/doc.aspx?mcl-421-28.

17

See “Waiver of Seeking Work,” Mich. Admin. Code r. 421.216, https://www.law.cornell.edu/regulations/michigan/Mich-Admin-

Code-R-421-216.

18

“Unemployment Insurance Protections in Response to COVID-19,” National Employment Law Project, March 27, 2020,

https://www.nelp.org/publication/unemployment-insurance-protections-response-covid-19-state-developments/.

19

“State Laws,” 42 U.S.C. §503(A)(12), https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/42/503.

20

“Unemployment Insurance Program Letter No. 5-13,” US Department of Labor Employment and Training Administration, UIPL No.

5-13, 2013, https://www.dol.gov/agencies/eta/advisories/unemployment-insurance-program-letter-no-05-13.

21

Id.

22

“Approval of State Laws,” 26 U.S.C. §3304(8), https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/26/3304.

23

“Definitions,” 26 U.S.C. §3306(V), https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/26/3306.

24

See “Comparison of State UI Laws 2021, Ch. 5 Nonmonetary Eligibility,” US Department of Labor, 2021,

https://oui.doleta.gov/unemploy/pdf/uilawcompar/2021/nonmonetary.pdf.

25

“NEW Information for filing for unemployment, mandatory filing by employers for partial claims, and reemployment services,”

Georgia Department of Labor, March 27, 2020,

https://dol.georgia.gov/blog/new-information-filing-unemployment-partial-claims-

and-reemployment-services.

26

“Approval of State Laws.”

27

“Definitions.”

28

See “Waiver of Seeking Work,” Mich. Admin. Code R 421.216; see also “Fact Sheet 161 - Waivers of Unemployment Insurance

Eligibility Requirements,” Michigan Department of Labor and Economic Opportunity,

https://www.michigan.gov/leo/bureaus-

agencies/uia/tools/fact-sheets/waivers-of-unemployment-insurance-eligibility-requirements for ideas on other types of work

search exemptions that could be available.

29

See the policy advocacy brief on partial benefits at https://www.nelp.org/publication/partial-benefits/

30

“Who chooses part-time work and why?,” US Bureau of Labor Statistics Monthly Labor Review, March 2018,

https://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2018/article/who-chooses-part-time-work-and-why.htm; “Persons with a Disability: Labor Force

Characteristics—2021,” US Bureau of Labor Statistics, News Release, February 24, 2022,

https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/disabl.pdf.

31

“Comparison of State UI Laws 2021, Ch. 5 Nonmonetary Eligibility,” Table 5-16.

32

The states that require just one to two work search activities to be reported each week are AK, AR, DE, DC, ID, IA, MI, MT, NM, OH,

OK, PA, SC, SD, and WY. “Comparison of State Unemployment Insurance Laws 2021,” US Department of Labor, 2021,

https://oui.doleta.gov/unemploy/pdf/uilawcompar/2021/complete.pdf.

33

Wentworth, “Closing Doors on the Unemployed.”

34

“Comparison of State UI Laws 2021, Ch. 5 Nonmonetary Eligibility,” Table 5-15.

35

Over the past several years, the National Association of State Workforce Agencies has been working with a British group called

Behavioral Insights to help state agencies use proactive rather than punitive methods to encourage work search compliance and

reduce improper payments. See Behavioral Insights UI Toolkit and training video at

https://library.naswa.org/bitoolkit.

36

Marta Lachowska et al., “The Effects of Eliminating the Work Search Requirement on Job Match Quality and Other Long-Term

Employment Outcomes,” Upjohn Institute, January 1, 2015,

https://research.upjohn.org/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1073&context=externalpapers/; Klepinger et al., “Effects of

Unemployment Insurance Worksearch Requirements: The Maryland Experiment,” Industrial and Labor Relations Review 56, no. 1

(October 2002): 3–20,

http://pinguet.free.fr/klepinger2002.pdf; Duncan McVicar, “The Impact of Monitoring And Sanctioning On

Unemployment Exit And Job-Finding Rates,” IZA World of Labor, June 2020, https://wol.iza.org/uploads/articles/540/pdfs/impact-

of-monitoring-and-sanctioning-on-unemployment-exit-and-job-finding-rates.pdf.

37

Klepinger et al., “Effects of Unemployment Insurance Worksearch Requirements.”

38

Orley Ashenfelter, David Ashmore, and Olivier Deschênes, “Do Unemployment Insurance Recipients Actively Seek Work? Evidence

from Randomized Trials in Four U.S. States,” Journal of Econometrics 125, no. 1–2 (March–April 2005): 53–75,

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0304407604000740.

NELP | WORK SEARCH | NOVEMBER 2023

13

39

Marios Michaelides et al., “Impact of the Reemployment and Eligibility Assessment (REA) Initiative in Nevada,” IMPAQ

International, LLC, January 2012,

https://wdr.doleta.gov/research/FullText_Documents/ETAOP_2012_08_REA_Nevada_Follow_up_Report.pdf.

40

Wentworth, “Closing Doors on the Unemployed.”

41

Id.

42

Minhoff, “Racist Roots of Work Requirements.”

43

Joe Soss, Richard C. Fording, and Sanford F. Schram, Disciplining the Poor: Neoliberal Paternalism and The Persistent Power of Race

(University of Chicago Press, 2011).

44

Heidi Shierholz, “Nearly Three Years of a Job-Seekers Ratio Above 4-To-1,” Economic Policy Institute, January 10, 2012,

https://www.epi.org/publication/job-seekers-ratio-above-4-to-1/.

45

“Transcript: Hearing on Moving from Unemployment Checks to Paychecks: Assessing the President’s Proposals to Help the Long-

Term Unemployed,” US House of Representatives Committee on Ways and Means,

October 6, 2011, https://gop-waysandmeans.house.gov/hearing-on-moving-from-unemployment-checks-to-paychecks-assessing-

the-presidents-proposals-to-help-the-long-term-unemployed/.

46

The reference to Anthony Garcia was first raised by Representative Geoff Davis of Kentucky, the same member of Congress who

infamously referred to President Obama as “boy.” “Unemployment Checks to Paychecks: Implementing Recent Reforms,” House

Hearing, 112 Congress, US Government Publishing Office,

https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-

112hhrg78665/html/CHRG-112hhrg78665.htm.

47

Traub and Diehl, “Reforming Unemployment Insurance.”

48

Andrew Perrin, “Mobile Technology and Home Broadband 2021,” Pew Research Center, June 3, 2021,

https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2021/06/03/mobile-technology-and-home-broadband-2021/.

49

Klepinger et al., “Effects of Unemployment Insurance Worksearch Requirements.”

50

“Comparison of State Unemployment Insurance Laws 2021,” Table 5-15.

51

USDOL measures work search compliance through a state agency internal audit program called Benefit Accuracy Measurement

(BAM). The BAM uses a relatively small sample (less than 500 per year depending on the size of the state) of actual claims to test for

improper payments. See “Benefit Accuracy Measurement Program Fact Sheet,” US Department of Labor, Employment and Training

Administration,

https://oui.doleta.gov/unemploy/bam/2002/bam_fact.asp.

52

“Unemployment Insurance: Transformation Needed to Address Program Design, Infrastructure, and Integrity Risks,” GAO, June

2022, 31,

https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-22-105162.pdf.

53

“Benefit Accuracy Measurement State Data Summary Improper Payment Information Act Performance Year 2020,” US Department

of Labor, Employment and Training Administration,

https://oui.doleta.gov/unemploy/bam/2020/IPIA_2020_Benefit_Accuracy_Measurement_Annual_Report.pdf.

© 2022 National Employment Law Project. This report is covered by the Creative Commons “Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs”

license fee (see http://creativecommons.org/licenses). For further inquiries, please contact NELP (nelp@nelp.org).