a

b

Real Estate

Focus

Chief Investment Office WM

2018

3

UBS Real Estate Focus 2018

Editorial

Dear reader,

To this day, spinach enjoys the reputation of being a miraculous source of iron.

For this reason, generations of children have been and still are repeatedly

forced to eat the green leafy stu. This myth is based on an error, the origin

ofwhich goes back over 100 years. A scientist at that time is said to have made

a mistake with the decimal point, which attributed to the vegetable ten times

its actual iron content. The iron content of spinach is a prime example of an

error that has been disseminated without challenge and thus has become

taken for granted.

The debate surrounding fully autonomous vehicles and their impact on the

realestate market shows some parallels with the spinach legend. In this case,

itis not a matter of the undisputed iron content of such vehicles, but rather

the one-sided manner in which the debate is being conducted. As in the case

of the iron content of spinach, hardly a single analysis allows for any doubt

that we will soon be traveling around in fully autonomous vehicles. It is beyond

question that the assistance systems are becoming ever more sophisticated,

thanks to technological advances. But in reality, it is still far from certain

whether and, if so, how private road transport can be fully automated. The

visionaries also seem be in agreement about the impact of fully autonomous

vehicles on the property markets, advising us to align our real estate invest-

ments accordingly as of now. A recommendation which is in our opinion (still)

being made on shaky grounds.

The special theme of this year’s UBS Real Estate Focus does indeed deal with

tomorrow’s mobility and its consequences for the property markets. But so that

in facing today’s challenges you don’t have to consume a regular ration of

spinach like the cartoon gure Popeye, we have also focused again this year on

the market trends which are currently the most important ones for you.

We hope you nd this an engaging read.

Daniel Kalt

Chief Economist Switzerland

Claudio Saputelli

Head Global Real Estate

4 UBS Real Estate Focus 2018

Content

6 Change in mobility

Not a game changer

8 Accessibility

Access to activities is key

10 Autonomous cars

Revolution in the real estate

market?

12 Condominiums and single-family

homes

Footprints keep shrinking

16 Apartment buildings

No longer at any price

20 Mortgages as an asset class

More money from institutional

investors

23 Investment crowdfunding

Higher returns with higher risk

UBS Real Estate Focus 2018

This report has been prepared by

UBS Switzerland AG. Please see the

important disclaimer at the end of the

document. Past performance is not an

indication of future returns. The market

prices provided are closing prices on the

respective principal stock exchange.

Publisher

UBS Switzerland AG

Chief Investment Ofce WM

P.O. Box, CH-8098 Zurich

Editor in Chief

Elias Hafner

Editor

Andrew DeBoo

Editorial deadline

11 January 2018

Translation

24translate GmbH, St. Gallen

Desktop publishing

Margrit Oppliger

Werner Kuonen

Photos

Manuel Stettler Fotograe, Burgdorf

Cover photo

Community hall, Männedorf

Printer

galledia ag, Flawil, Switzerland

Languages

English, German, French, and Italian

Contact

Order or subscribe

UBS clients can subscribe to the print

version of UBS Real Estate Focus via their

client advisor or the Printed & Branded

Products mailbox:

Electronic subscription is also

available via Investment Views on the

UBS e-banking platform.

SAP-Nr. 83518E-1801

6

Mobility

12

Residential

5

UBS Real Estate Focus 2018

26 Retail space

Shopping malls reinvent

themselves

29 Ofce space

Prices (still) correcting

32 Hotel investments

Potential in the cities

35 Parking garages as investment

properties

Niche strategy without extra

yield

38 Real estate equities and funds

Not cheap

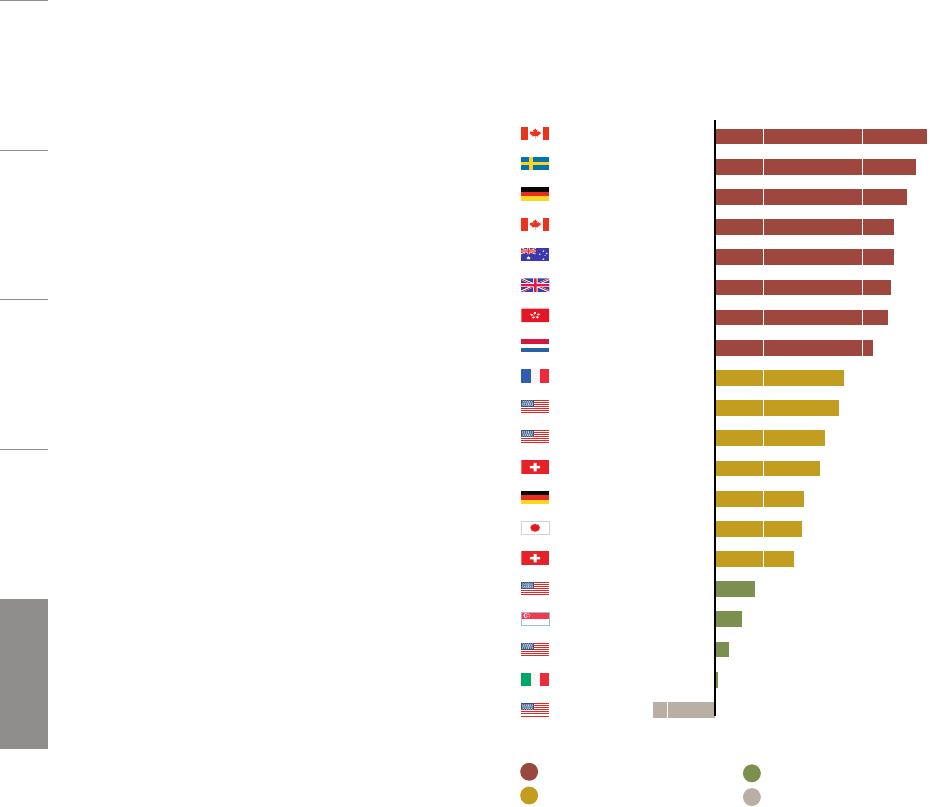

42 UBS Global Real Estate

Bubble Index

Superstars or bubbles?

46 Global market for direct

real estate investments

Where opportunities still reside

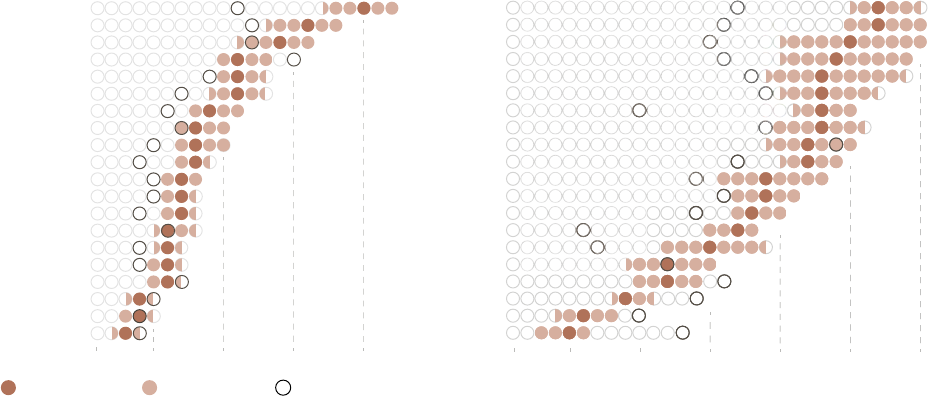

49 Impact of long-term

investment themes on global

real estate markets

Existing properties could

depreciate faster

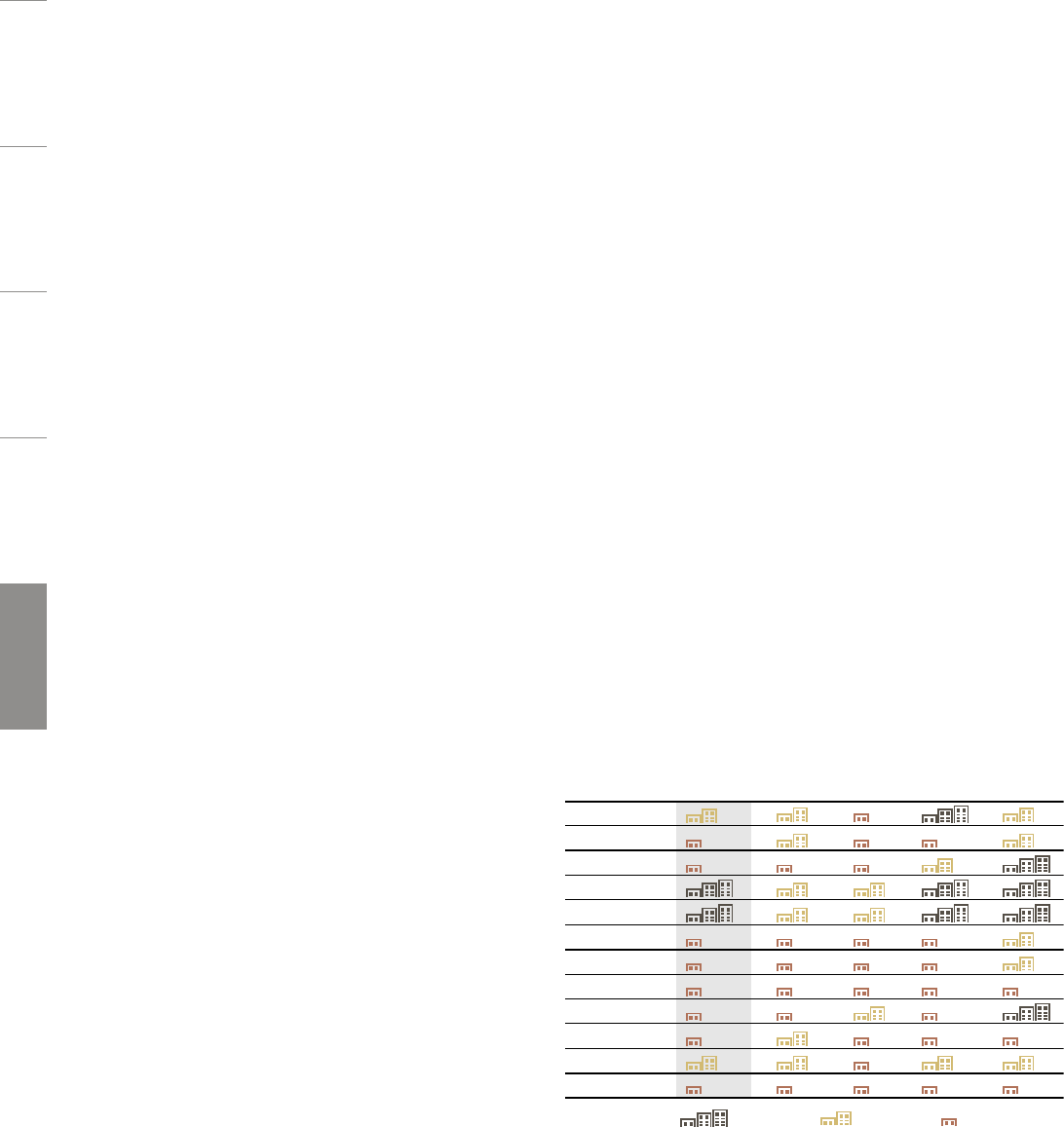

54 Overview and forecasts

26

Comm ercial

42

Global

38

L is te d

6 UBS Real Estate Focus 2018

The United Nations predicts that two thirds of

the world’s population will call a city home by

2050. A century ago, only 30% of people were

urban dwellers. Urbanization has made great

strides in Western countries. At the end of

2015, for example, around 84.5% of Swiss resi-

dents lived in urban areas, compared to less

than half the population in emerging and devel-

oping nations.

Urbanization and economic progress go hand in

hand. Productivity increases when people live

and work in cities. Also, cities can supply public

services more cheaply (such as electricity, water,

wastewater services, gas and telecommunica-

tions). Urbanization and the emergence and

development of metropolitan areas are essential

for economic growth and, ultimately, for pros-

perity.

Mobility is key to efciency

For an economy to reap the full benets of its

workforce’s potential, people have to be free to

move quickly and independently in its metropo-

lises. The challenges begin here. In 2013, two

thirds of total mobility was concentrated in

urban areas. If infrastructure development fails

to keep pace with current population trends,

people will spend more time sitting in city traf-

c. Trafc disruptions are already serious today.

With demand for mobility expected to triple by

2050, urban planners could face a nightmare

scenario of widespread trafc gridlock, with all

the negative social and economic consequences

that entails.

Intelligent mobility solutions more urgent

than ever

Current capacity constraints can partly be

blamed on urban development since the post-

war period, in which cars came to dominate cit-

ies. To counter this one-sidedness, it is necessary

to apply a more granular understanding of

urban mobility and planning. Ideally, the car

monoculture, in which cars in downtown areas

are usually stuck in trafc jams or parked in

space-hogging lots, will be replaced by a

broader menu of mobility alternatives where

public transit, non-motorized options – such as

pedestrian zones and bicycle lanes – and poten-

tially driverless cars (see page 10) will change

how people get around.

No change in daily travel time budget

Urban and development planning is highly com-

plex, but the consequences of future mobility

plans can be demonstrated quite simply using a

constant travel time budget. Cesare Marchetti

described this budget in 1994, positing that

people in dierent countries and cultures do

not change their average commute times over

decades (Marchetti’s constant). This observation

is based on an intriguing trend: people’s travel

time budgets do not decrease even as faster

travel options emerge. In France, for example,

the average travel speed has increased 3% a

year on average in the past 200 years. In other

words, when transportation gets faster, com-

muting distances get longer.

Not a game changer

Worldwide urbanization is continuing inexorably, and demand

for mobility is keeping pace. New solutions are needed to keep

limited trafc capacity from curbing economic growth. Property

values will only rise in regions that “move closer” from a time

perspective.

Change in mobility

Claudio Saputelli

Global Listed Commercial Residential Mobility

7

UBS Real Estate Focus 2018

Impact on the real estate market

No convergence of urban and rural prices

Marchetti’s constant is one of the most stable

mobility indicators around. On work days, com-

muters travel an average of 70 to 90 minutes in

the countries examined. So what are the impli-

cations for the real estate market?

First, demand will remain high for real estate

markets in urban centers and metropolitan

areas within the travel time budget, even if the

nature of mobility changes, as long as attractive

jobs are concentrated in cities.

Second, property values will rise in regions that

have “moved closer” to workplaces as a result

of mobility improvements or major trafc infra-

structure projects. This trend will drive urbaniza-

tion.

Third, mobility concepts of the future – particu-

larly driverless cars designed to reduce perceived

travel time – will not reduce the dierence

between property prices in city centers and

peripheral regions, particularly outside the travel

time budget. The unique diversity of mobility

oerings, the availability of innumerable ser-

vices and the dense concentration of knowl-

edge will always make major centers more

appealing than rural areas. In addition, major

centers within Marchetti’s constant oer access

to jobs in other (global) major centers thanks to

airports and direct rail connections.

Hans Wilsdorf Bridge, Geneva

“Despite the upcoming mobility

changes, demand for urban real estate

will remain high.”

8 UBS Real Estate Focus 2018

Global Listed Commercial Residential Mobility

Transportation accessibility is important for the

attractiveness of regions as places for people to

live and for companies to be based. Highly

accessible regions, aer all, have lower trans-

portation and time costs, and so are generally

more productive and thus more competitive

than their less accessible counterparts. No won-

der trafc and development planners are so

focused on maintaining or improving accessibil-

ity over the long term. There are two ways to

achieve this goal: the rst is to locate activity

destinations at or near residential areas, and the

second is to optimize transportation services

and infrastructure. In prosperous countries like

Switzerland, these two approaches oen go

hand in hand.

Improvement in almost every region

Accessibility is good in Switzerland in general,

and in most of its towns and municipalities. This

holds true not only within Switzerland, but also

compared to other countries, as various studies

report. Building more transportation routes has

improved accessibility, as have higher speed lim-

its, improvements to existing infrastructure (e.g.

increasing the number of connections) and

road-widening projects that have added extra

lanes.

The Gotthard Base Tunnel is the most recent

example of the large transportation infrastruc-

ture projects that have continuously boosted

accessibility in Switzerland. In fact, according to

BAKBASEL, accessibility has improved in virtually

every region of the country since 2005, with

respect to both public transit and private motor-

ized transportation. The centers of large cities

are the only exceptions; these are now less

accessible by private motor vehicle than they

were several years ago, as factors such as high

population growth nationwide have led to

chronically congested thoroughfares.

Good accessibility bolsters the real estate

market

Good regional accessibility is reected in local

property prices. However, it is impossible to

quantify this eect exactly. There is no univer-

sally accepted denition or methodical

approach for measuring accessibility, so it is

oen estimated based on simplied assump-

tions. Nonetheless, a survey of national and

international studies can be distilled into four

empirical ndings on how accessibility aects

property prices.

Access to activities

is key

Most Swiss locations are highly accessible, by both national

andinternational comparison. Real estate prices are generally

higher in centrally located regions with equally easy access via

public and private transportation. New trafc infrastructure

cannot always aect prices, however.

Claudio Saputelli

Accessibility

More accessible, not just

more mobile

“Mobility” is oen confused with “accessibility.”

Mobility describes whether, how oen and how

easily people, goods and services can move or be

transported. Accessibility, by contrast, is need

and destination-based. It focuses on the travel

times, costs, options, comfort and risks associ-

ated with access to key activity destinations

(work, education, shopping and recreation).

When transportation systems are designed to

meet a community’s needs, their main function

is to provide access to activity destinations at a

low cost and with the least eort possible. Trans-

portation and infrastructure policies should

therefore focus on improving accessibility instead

of merely increasing mobility.

9

UBS Real Estate Focus 2018

9,000

11,000

7,000

12,000

13,000

14,000

4,000

5,000

10,000

8,000

6,000

2004

02

0

04

060

Zurich

Geneva

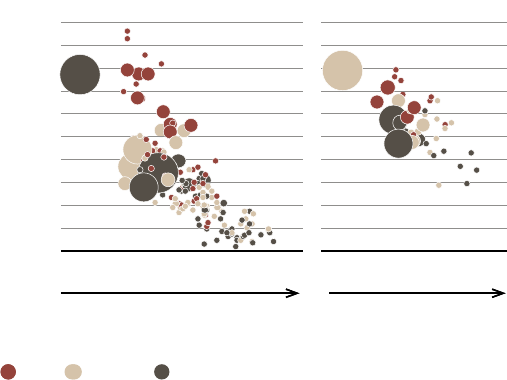

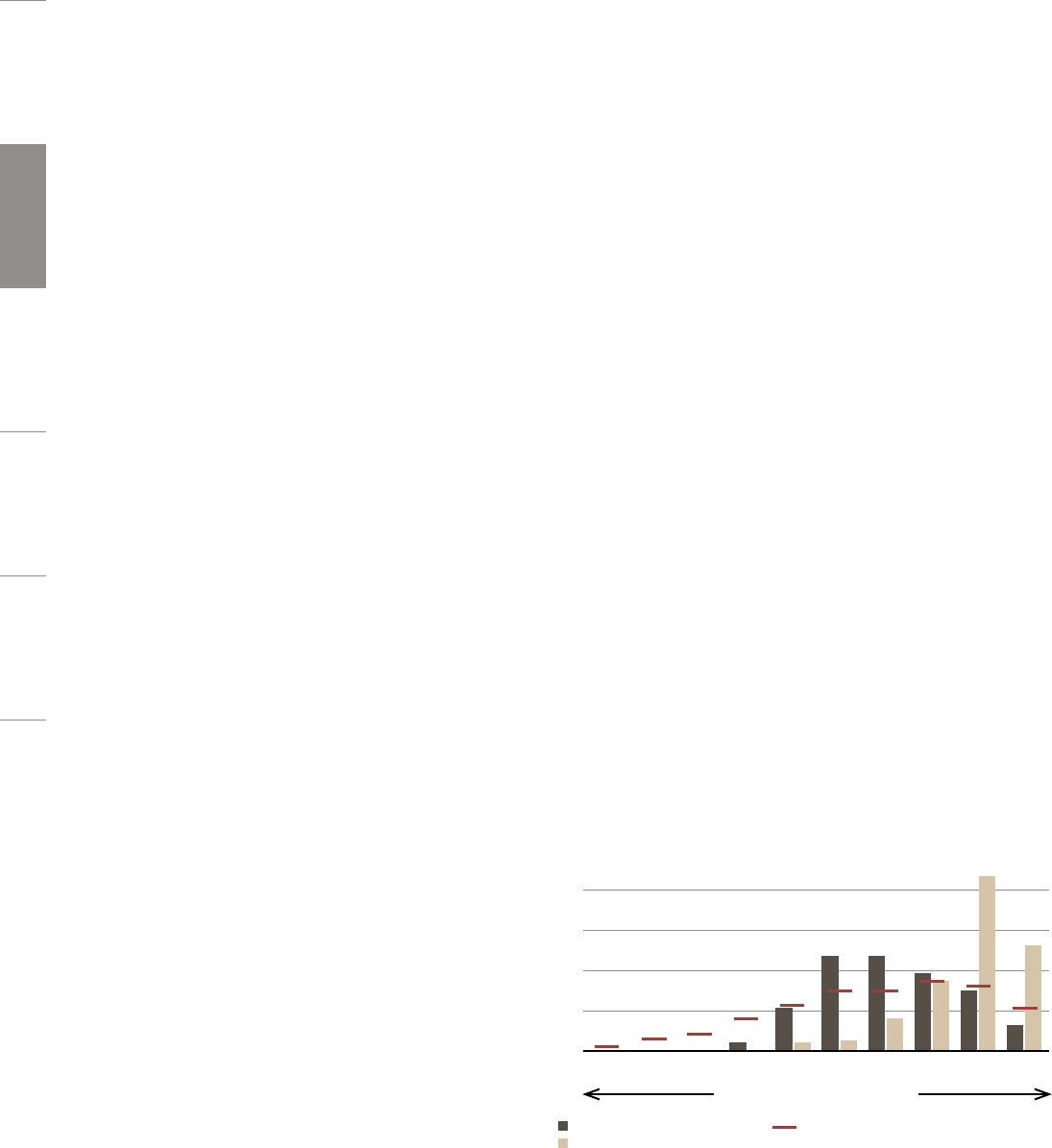

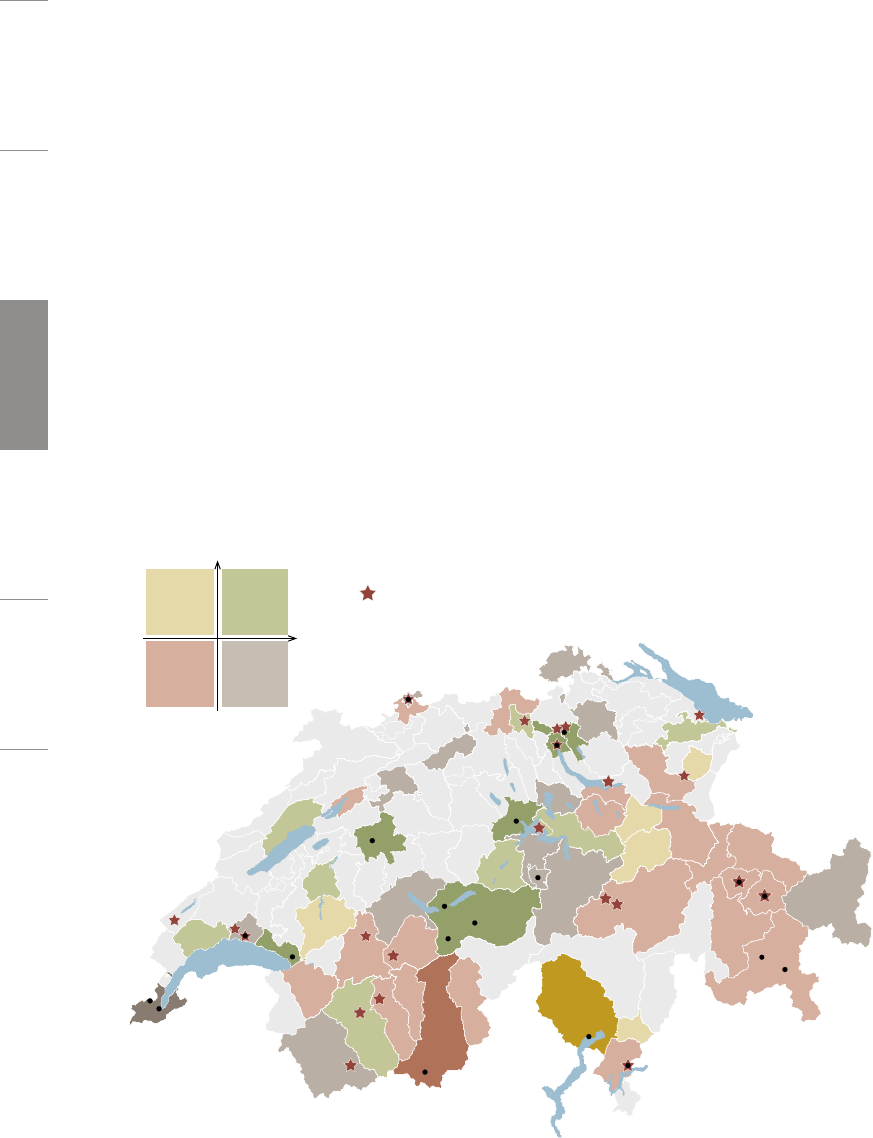

Prices rise as accessibility improves

Source: FSO, TranSol, Wüest Partner, UBS

Condominium prices (in CHF/m²) and accessibility (in minutes)*

Municipalities

in Canton Zurich

Travel time to Zurich

Municipalities

in Canton Geneva

Travel time to Geneva

Tax rates relative to canton municipalities

Low Medium High

* Average travel time with personal motor vehicle and public transportation to the r

espective centers;

population size class represented by circle size.

Travel time to central business district

One big driver of property prices is “centrality,”

i.e. the travel time to the nearest central busi-

ness district and the related opportunity cost

(loss of potential benets) of this time. Gener-

ally speaking, the farther away the central busi-

ness district, the lower the property prices.

However, other factors such as a town’s topo-

graphical location, supply and – particularly in

Switzerland – tax considerations can override

this eect and produce an entirely dierent out-

come.

Quality dierences between public and private

transportation

Regions that can be accessed just as well with

public transit systems as with private transporta-

tion tend to have higher real estate prices than

regions with qualitative dierences between

these two modes of transportation. Also, buyers

are willing to pay more for properties that are

easy to access with private vehicles than for

comparable properties that are more accessible

via public transportation. For that reason, prop-

erty prices tend to rise more in response to proj-

ects targeting private motorized transportation

than to projects to improve public transporta-

tion.

Travel time saved by transportation projects

Locations that are already highly accessible –

like big Swiss cities – do not have much room

for improvement. Even large transportation

projects can only lower travel times a little.

Smaller locations are a dierent proposition

entirely; they oen harbor greater potential. As

a result, property prices in more remote com-

muter locations tend to respond more to trans-

portation projects.

Regional development potential

Improved accessibility can stimulate the local

economy, encouraging home construction and

reviving the housing market. This does not hap-

pen automatically, though. Transportation infra-

structure projects can only contribute to eco-

nomic prosperity if the targeted region has

untapped potential of its own, or if the project

connects it to a larger, more dynamic economic

center.

10 UBS Real Estate Focus 2018

Imagine a world where robotic cars whisk you

from one place to the next. It is a much safer

world thanks to intelligent control soware,

lightning-fast reactions, tireless attentiveness,

better all-round visibility and strict adherence to

trafc laws. It is also a world without the stress

and wasted time that comes from battling city

trafc. Driverless cars pick you up at home and

transport you to your destination while you

work or, depending on the car’s features, catch

up on sleep. It may sound utopic now, but it

could become everyday reality. With near

weekly newsbites about autonomous cars, the

automotive industry implies that these vehicles

will start appearing in showrooms in only a few

years’ time.

Forecasts tell us that perceived travel times will

shrink to virtually zero. As a result, motorists

will be willing to drive more frequently and

cover longer distances. Car movements will

increase signicantly too, as unoccupied vehi-

cles roam around picking up passengers or per-

forming other activities. Also, large numbers of

non-vehicle owners – the elderly, disabled, chil-

dren, etc. – will likely adopt driverless cars.

Many questions remain unanswered

Driverless cars are still a long way from becom-

ing widespread though; too many hurdles still

lie ahead. The ethics of programming algo-

rithms to resolve life-or-death questions, for

example, is particularly difcult. People are wary

of accepting actions taken by autonomous

technology that may result in injury or death,

even if autonomous technology has a better

track record statistically than human drivers.

Also, lawmakers have to establish the legal

basis for the use of driverless cars. Germany, for

example, passed a bill in April 2016 that puts

the ultimate responsibility for accidents on the

human sitting in the driver’s seat, if there is any

doubt. As a result, drivers have no choice but to

constantly monitor the system, largely eliminat-

ing the touted advantages of fully autonomous

vehicles.

Technical reliability has been elusive too. None

of the current assistance systems work aw-

lessly. Road sign recognition – for example, the

technology that shows drivers the maximum

legal speed – regularly ceases to work when

signs are dirty. Reading cameras are also partic-

ularly prone to fail due to rain, ice or dirt, or

when the sun is low.

Impact on property markets

Urban parking lots would be relocated

It is currently unclear whether, when and how

autonomous vehicles will change how we get

around. That has not dammed the rise of

reports on how driverless vehicles are poised to

completely disrupt property markets and force

real estate investors to rethink their investment

strategies. They forecast the following big

changes if fully autonomous cars become a

reality one day:

Many people could decide to purchase trips in

an autonomous vehicle instead of owning one

or more cars. This would lower the demand for

garages, parking spaces and driveways; existing

space would be repurposed. Even large down-

town parking garages would become obsolete,

because autonomous cars would either be con-

stantly running or parked in large, fully auto-

matic parking systems on the city periphery.

Revolution in the

real estate market?

Fully autonomous vehicles – or rather, the technology for

them– are almost here. Unclear, however, is how autonomous

driving will actually work in a normal street environment.

Realestate investors betting on big changes in mobility behav-

ior are taking a huge risk.

Claudio Saputelli

Autonomous cars

Global Listed Commercial Residential Mobility

11

UBS Real Estate Focus 2018

Access roads to big apartment complexes,

ofces and retail outlets would have to be rede-

signed to allow large numbers of people to get

in and out of cars. Gas stations would also

come in for change (Switzerland currently has

around 3,400), since autonomous cars would

be maintained and lled up in eets at central

locations. Travel patterns would alter as well.

The ability to relax and even sleep in autono-

mous cars would eliminate the need for travel-

ers to interrupt their trip and spend the night in

hotels close to main trafc arteries.

Betting on a vision of the future

The rise of fully autonomous vehicles is

expected to revolutionize the property market,

which is why governments and real estate

developers are already being encouraged to

devise exible long-term development strate-

gies. However, they are also being told that cit-

ies need even more parking capacity – at least

in the short term. The recipe for success is

therefore to build parking garages that can be

easily converted to retail or other uses over the

long term. Of course, real estate developers

would be well advised to pursue exible long-

term development strategies even without

autonomous vehicles.

Optimistically, it will probably take a decade or

more before driverless cars become a reality and

can be used anywhere, at any time and at least

as safely as human-operated vehicles. Once that

day arrives, another question will arise: How

many people will still drive themselves, either

because they enjoy sitting behind the wheel or

do not trust the machine? Clearly, betting now

on a brick-and-mortar strategy fully aligned

with autonomous vehicles is risky.

Sour

ce: mobilegeeks.de, UBS

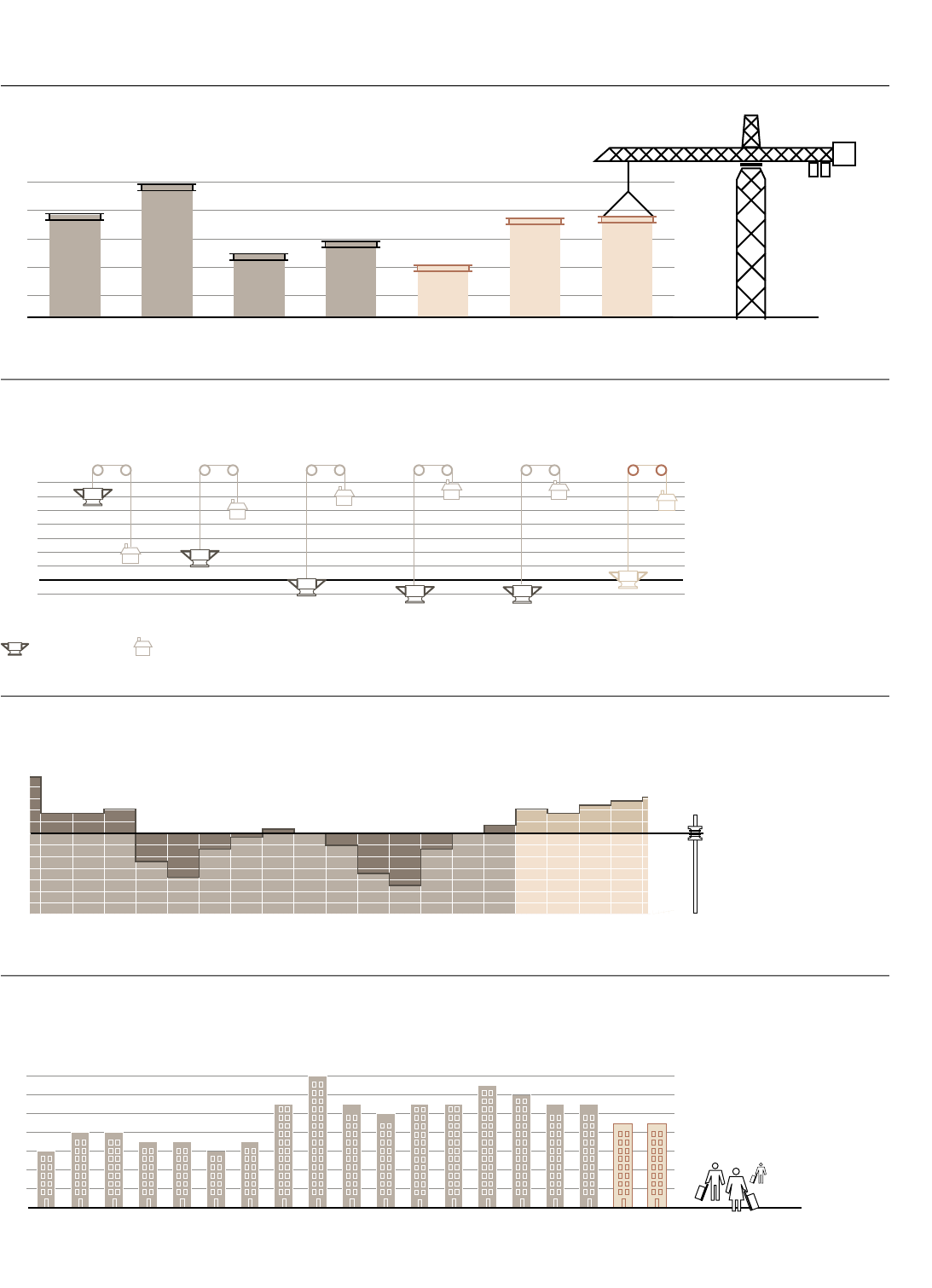

Driver’s

tasks

Vehicle’s

tasks

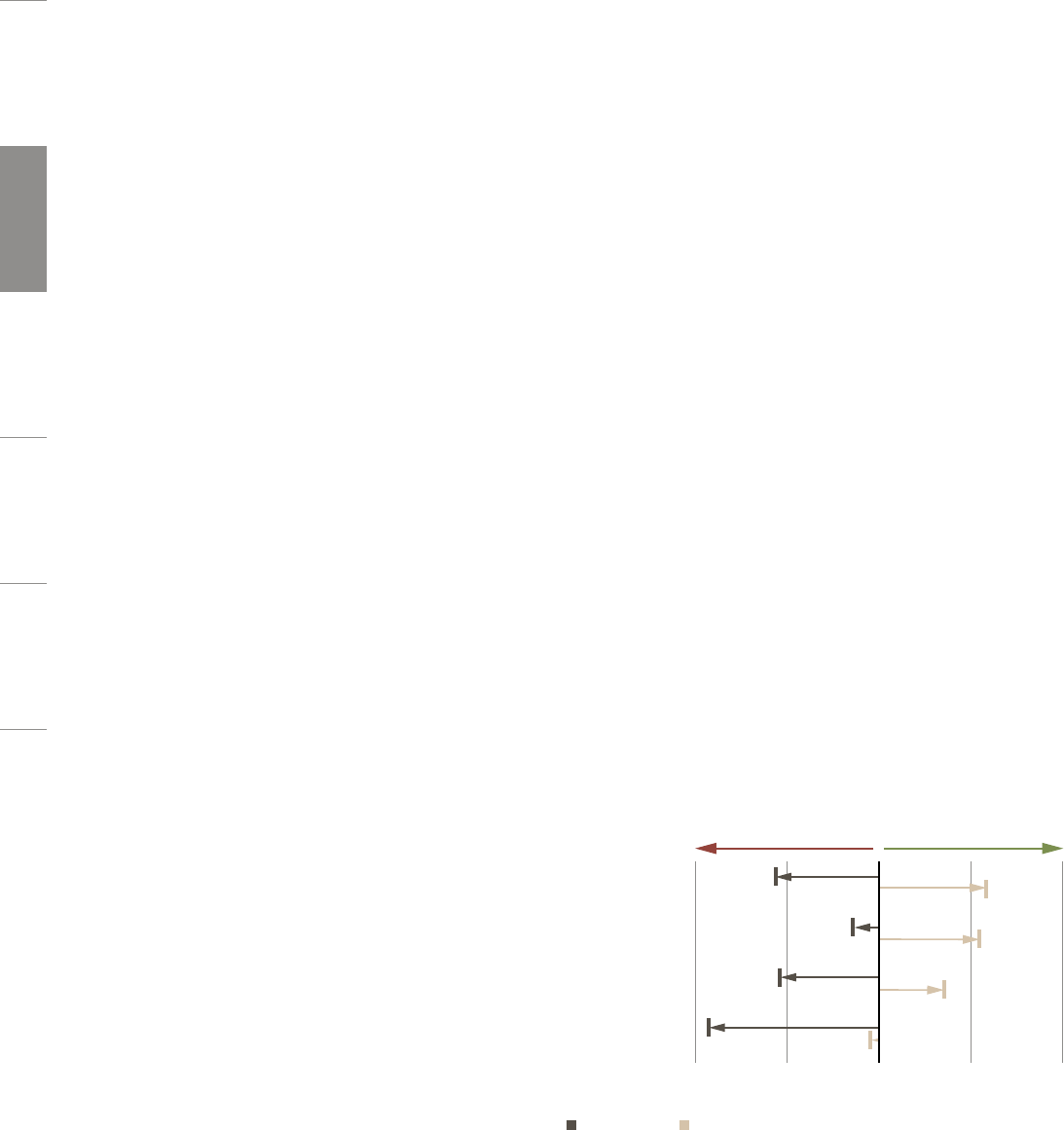

01 2345

Driver drives

and steers

the vehicle

Driver does not

have to operate

pedals

Vehicle can

accelerate and

decelerate

Vehicle can

accelerate,

decelerate

and turn

Vehicle can

accelerate,

decelerate

and turn,

warns driver

early on

Vehicle can

accelerate,

decelerate,

turn and

minimize

driving risk

Vehicle

performs

all

functions

Driver does not

have to operate

pedals or

steering wheel,

has a super-

visory function

Driver only

has to take

the controls

if needed

Driver

can take

the controls

Unassisted Assisted

Partially

automated

Highly

automated

Autonomous Driverless

A long road to full automation

The 5 stages of motor vehicle automation

Vehicle does

not have any

control functions

No driver

12 UBS Real Estate Focus 2018

Last year did not bring many new drivers for

theowner-occupied housing market. Mortgage

interest rates remained stable, population

growth dropped below 1%, and rental apart-

ments became cheaper. Home prices, however,

rose slightly yet again in 2017. Condominium

prices remained stable year-to-year, but prices

of single-family homes increased roughly 2%.

Home prices expected to increase slightly

The owner-occupied home market is mainly

buoyed by low mortgage rates. The cost of

owning your own home in Switzerland (interest

costs, maintenance and provisions) is currently

around 15% lower than the cost of renting a

comparable property. With loan-to-values at

80%, the resulting return on equity is over 4%.

This situation is unprecedented, at least in the

current real estate cycle. Ten years ago, housing

was avery popular investment: the cost of own-

ing ahome exceeded the cost of renting by

40%. This implies that investors expected prices

to increase at the time. In fact, purchase prices

had to increase at least 2% each year to oset

the additional cost of ownership compared to

rental (which was exceeded). The current sav-

ings, by contrast, provide a buer against a

market correction: home buyers would still be

ahead nancially if prices corrected by 0.5%

a year.

This buer is not expected to be exhausted in

2018. Home ownership costs will remain low;

the robust economy has bolstered demand for

homes. Home construction should also remain

at last year’s level, which was 15–20% lower

than in 2014. We expect single-family home

prices to increase slightly. Condominium prices,

however, will likely stagnate since they face

stier competition from declining rents. Abso-

lute purchase price amounts continue to limit

nancing availability, driving demand for small

apartments and maintaining buyers’ willingness

to pay for lesser-quality properties.

Condominiums were in the lead

Prices for condominiums have risen faster than

those for single-family homes in the current real

estate cycle. When adjusted for ination, con-

dominium prices in the available price indexes

increased an average of 2.4% a year over the

last 20 years, while those of single-family

homes climbed a mere 1.9%. Much of this dif-

ference can be put down to three factors.

Footprints keep

shrinking

Single-family homes have gained ground over condominiums.

Stier competition with rental apartments is causing condo-

minium prices to stagnate. Urban concentration will slow new

construction of single-family homes, but will have little impact

on prices.

Maciej Skoczek and Matthias Holzhey

Condominiums and single-family homes

Global Listed Commercial Residential Mobility

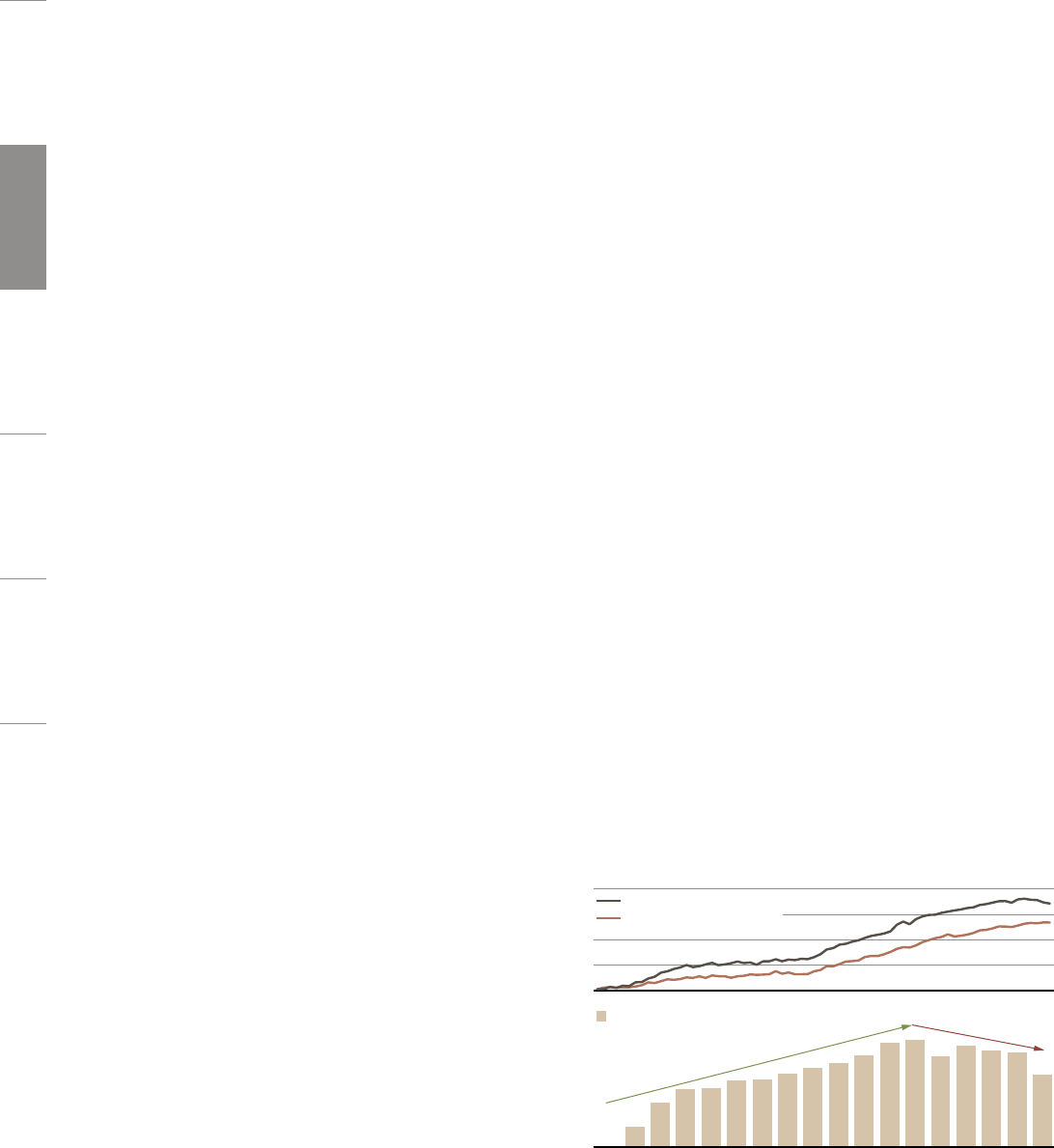

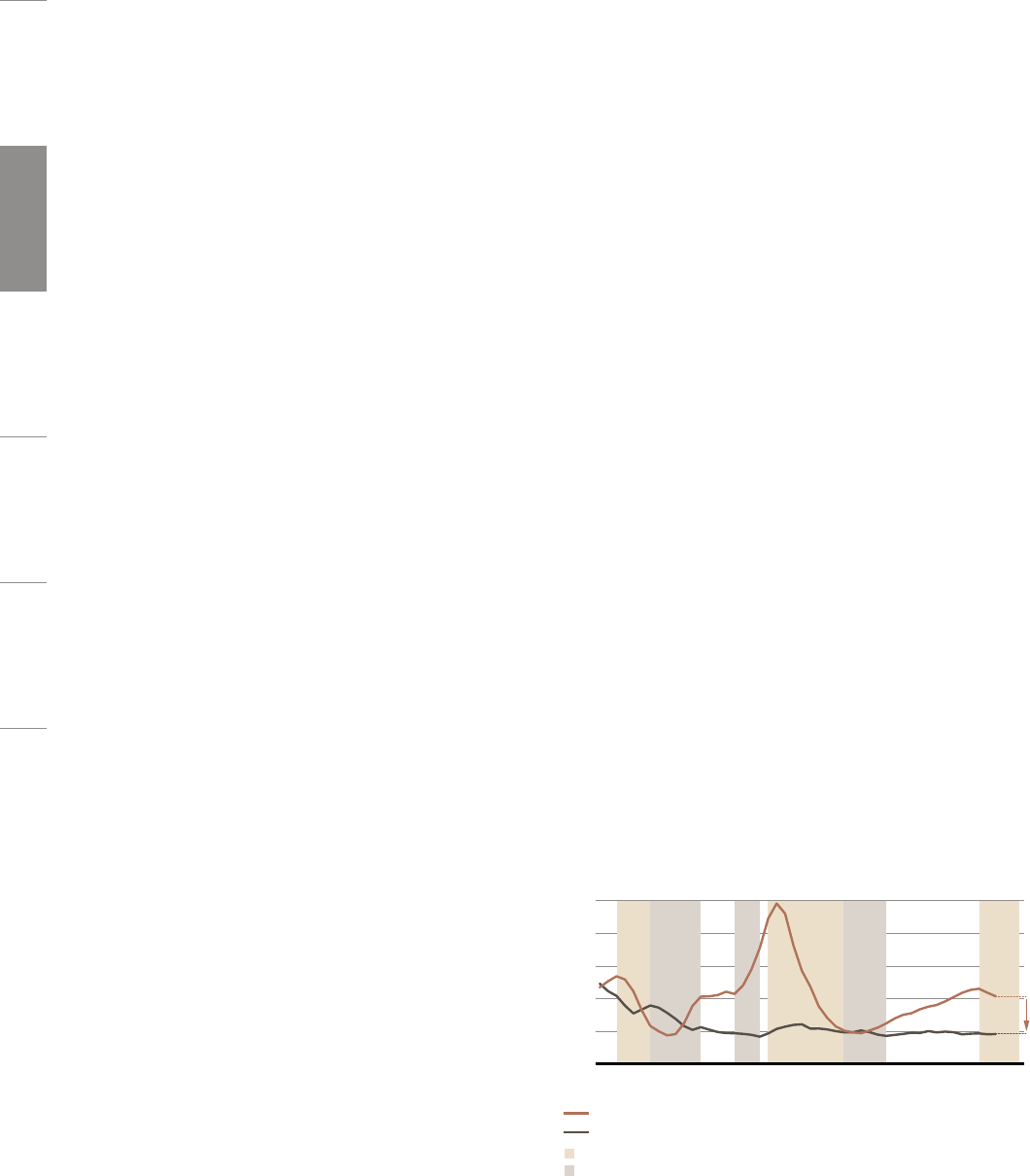

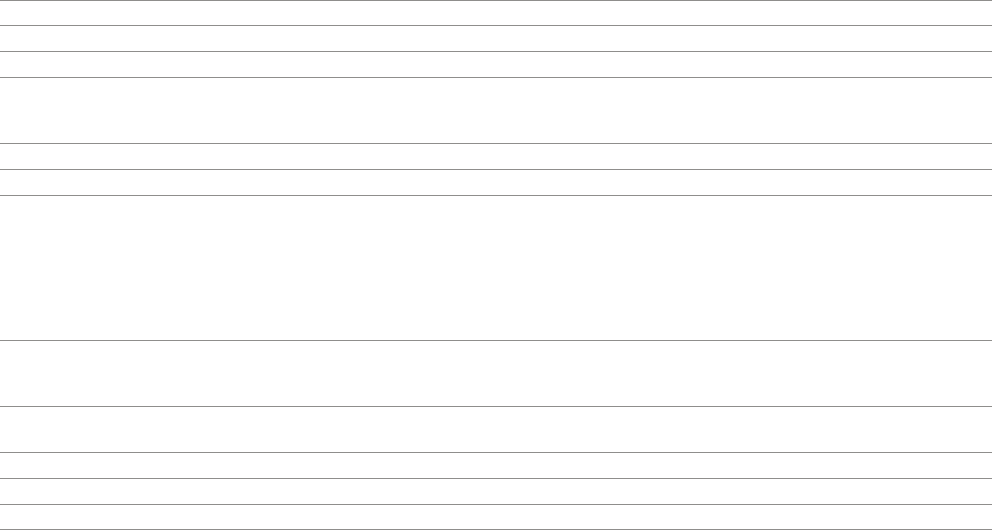

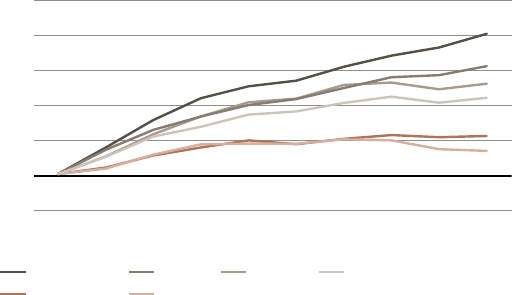

120

160

180

140

100

2015 201720072005 2011200920032001 2013

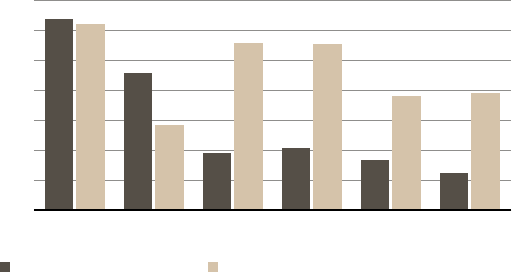

Parallel long-term price behavior

in the two market segments

Source: Wüest Partner, UBS

Inflation-adjusted asking prices (index 2000=100) and cumulative

difference in price change rates between condominiums and single-family

homes (in percentage points)

Condominiums

Single-family homes

Difference in price increases (cumulative)

5

15

10

0

+15 percentage points

–5 percentage points

13

UBS Real Estate Focus 2018

Swiss House XXII, Preonzo (Bellinzona), Architecture rm: Davide Macullo Architects

Single-family homes are too big

The average single-family home has around 170

square meters of living space. With purchase

prices averaging over CHF 1 million, the pool of

possible buyers is limited to 20% of all house-

holds. This shis demand toward condomini-

ums, which cost less than CHF 800,000 on

average. This theory is supported by the fact

that prices for relatively small condominiums

have risen faster than for condominiums over

150 square meters in size.

Single-family homes have worse macro

locations

Condominiums, whether new or pre-existing,

are usually found at better macro locations than

single-family homes. A quarter of all condomini-

ums are found at prime locations, compared to

a h of single-family homes. The annual price

increase at these locations was 1% higher than

the national average over the last 10 years.

Also, the construction boom in condominiums

has improved condominium construction quality

relative to single-family homes. Only a quarter of

all the owner-occupied homes built in recent

years are single-family homes. And modern con-

dominiums are comparable to single-family

homes in terms of comfort, privacy and sound

insulation.

Better rentability favors condominiums

Condominiums remain very popular invest-

ments. The percentage of loan applications

intended for buy-to-rent investments has nearly

doubled since 2007 and has hovered at 18–20%

of all housing loan applications for several years.

Small and medium-sized apartments in urban

centers and metropolitan areas in particular are

ideal investment vehicles for small investors. The

freedom to switch between living in the prop-

erty or renting it out justies the premium on

condominiums over single-family homes.

“Only a quarter of owner-occupied

homes built are single-family homes.”

14 UBS Real Estate Focus 2018

Urban centers

and metropolitan

areas

High-income

communities

Peri-urban

communities

Rural

communities

100–5–10 5

1995–2005

2005–2015

Uncontrolled proliferation

of settlements Densification

* According to the FSO’s area statistics as of December 15, 2017

Minimal densification in rural areas

Source: FSO, UBS

Difference between changes in population and changes in building area*,

by community type, in percentage points

Size, location and rentability dierences will

impact relative price trends in the future, too. In

the long term, however, the single-family home

market will be determined by two trends: densi-

cation and aging.

Densication aiming to reverse the trend

Higher oor area ratios mean higher property

values. Single-family homes seem perfectly

poised to prot from urban concentration, also

known as densication, because they occupy a

relatively large piece of land. So far, however,

home values have not risen much outside the

city centers.

No incentives for densication in rural areas

Most single-family homes are located in rural

areas. According to the data, developed areas

have not grown denser at all in the last 10years;

building space increased around 11%, on par

with population growth. Developers simply had

no incentives to densify; land was available and

relatively cheap. Only in city centers and high-in-

come communities did densities increase as high

land prices made it worthwhile to pack more

housing units into the same parcel of land.

Building space thus grew only half as fast as the

population. However, more single-family homes

were built than demolished between 2011 and

2015, even in high-income communities and city

centers. This is because, in most communities, it

only pays o to demolish and replace condo-

miniums if the oor area ratio can accommodate

a doubling of residential oor space.

Spatial Planning Act discourages new construc-

tion of single-family homes

Densication entails using undeveloped oases

within built-up areas as well as “unused devel-

opment rights,” which arise when the actual

built oor space is less than the legally permit-

ted oor space. According to a study by ETH

Zurich and the Federal Ofce for Spatial Devel-

opment, these “internal reserves” could easily

accommodate over a million residents. But den-

sication is not mandatory. Except for the

greater Zurich area, virtually every Swiss region,

including Geneva and Basel, has enough unde-

veloped, properly zoned land to absorb the next

decade of population growth without densify-

ing.

However, Switzerland’s new Spatial Planning

Act aims to use these “internal reserves.” It

gives precedence to the use of inll housing in

developed rural and metropolitan areas over an

increase in oor area ratios. Densication will

take place by packing as much oor space as

possible on such land, which will make new sin-

gle-family home construction difcult.

New condominiums continue to replace single-

family homes with extensive unused develop-

ment rights in upmarket locations. However,

these properties are already selling at a premium

as investment properties or status symbols. In

addition, the new Spatial Planning Act reduces

the net nancial gains from zoning changes by

levying a value-added tax of at least 20% on

property value increases attributable to new

zoning. Most cantons already levy value-added

tax on gains attributable to an upgrade in zon-

ing classications. Taken together, these trends

mean the supply of single-family homes will

grow more slowly in the future than it has thus

far.

Global Listed Commercial Residential Mobility

15

UBS Real Estate Focus 2018

Demographic change causes glut of single-

family homes

Over the medium to long term, however, the

lower supply of single-family homes will not be

enough to turn the price tide permanently. Until

2030, the main buyer group of large residential

units will grow at half the rate as the overall

population due to aging. In fact, demand for

single-family homes is expected to shrink in the

mountainous cantons of Central Switzerland,

Appenzell Innerrhoden and Grisons.

In other words, single-family home prices,

which have outperformed condominium prices

since 2014, are probably about to reach the end

of their rally. Prices in both market segments

should generally track each other closely over

the long term. Fierce competition and relatively

high transparency in the home market will pre-

vent prices in both segments from decoupling

in the long run.

Comparison of asking and

transaction price indexes

Price indexes based on asking prices and those

based on transaction prices should remain

essentially identical in the long term. In the past

10 years, however, transaction price indexes

have gained about 15 percentage points more

than asking price indexes. There are three rea-

sons for this dierence:

(1) In periods of fast-rising demand, transaction

prices are bid up higher than advertised

prices. This is likely what happened at times

in Swiss hot spots. Sellers, however, are

quick to adapt their expectations to changed

market realities.

(2) Transaction records make a more exact qual-

ity adjustment possible. In other words,

prices are adjusted for variations in quality,

such as micro location or building condition.

Since micro locations have deteriorated

among sold properties in the last ve years,

the adjustments have increased transaction

price indexes.

(3) Transaction price indexes weight expensive

regions more heavily. Steeper price increases

at good locations since 2000 have contrib-

uted to the decoupling of transaction prices.

16 UBS Real Estate Focus 2018

Asking rents have only dropped moderately, despite rapidly

increasing vacancy rates. This is partly for psychological rea-

sons. However, the downward trend should accelerate in the

next three years. Prices for apartment buildings have peaked,

and property values could decline if central banks do not

mount a sustained intervention.

Competition in the rental market is getting even

ercer. As of mid-2017, 2.4% of all rental apart-

ments were vacant. This level was last exceeded

in 1998, when 2.8% of rental apartments stood

empty. So far, however, the vacancy rate has

not scared o investors; the number of newly

approved units has declined very little in recent

quarters. This year, the total housing stock is

expected to increase 1.1%.

Vacancy rate poised to hit all-time high

Residential construction is virtually unchanged,

while additional demand is dropping. Net immi-

gration is expected to reach nearly 60,000 this

year, meaning that some 10,000 fewer addi-

tional apartments will be needed than in 2013.

The decline is entirely due to lower net immigra-

tion from EU countries, which has shrunk from

75% to 60% of total immigration in the last

four years.

Several factors are driving this trend. The eco-

nomic recovery in the Eurozone, especially on

the Iberian Peninsula, has slashed net immigra-

tion from Spain and Portugal to negligible levels

in the last ve years. But Switzerland’s weak

labor market has lost its allure, too. If construc-

tion and population trends remain the same,

the vacancy rate will reach a new record high by

2019 at the latest.

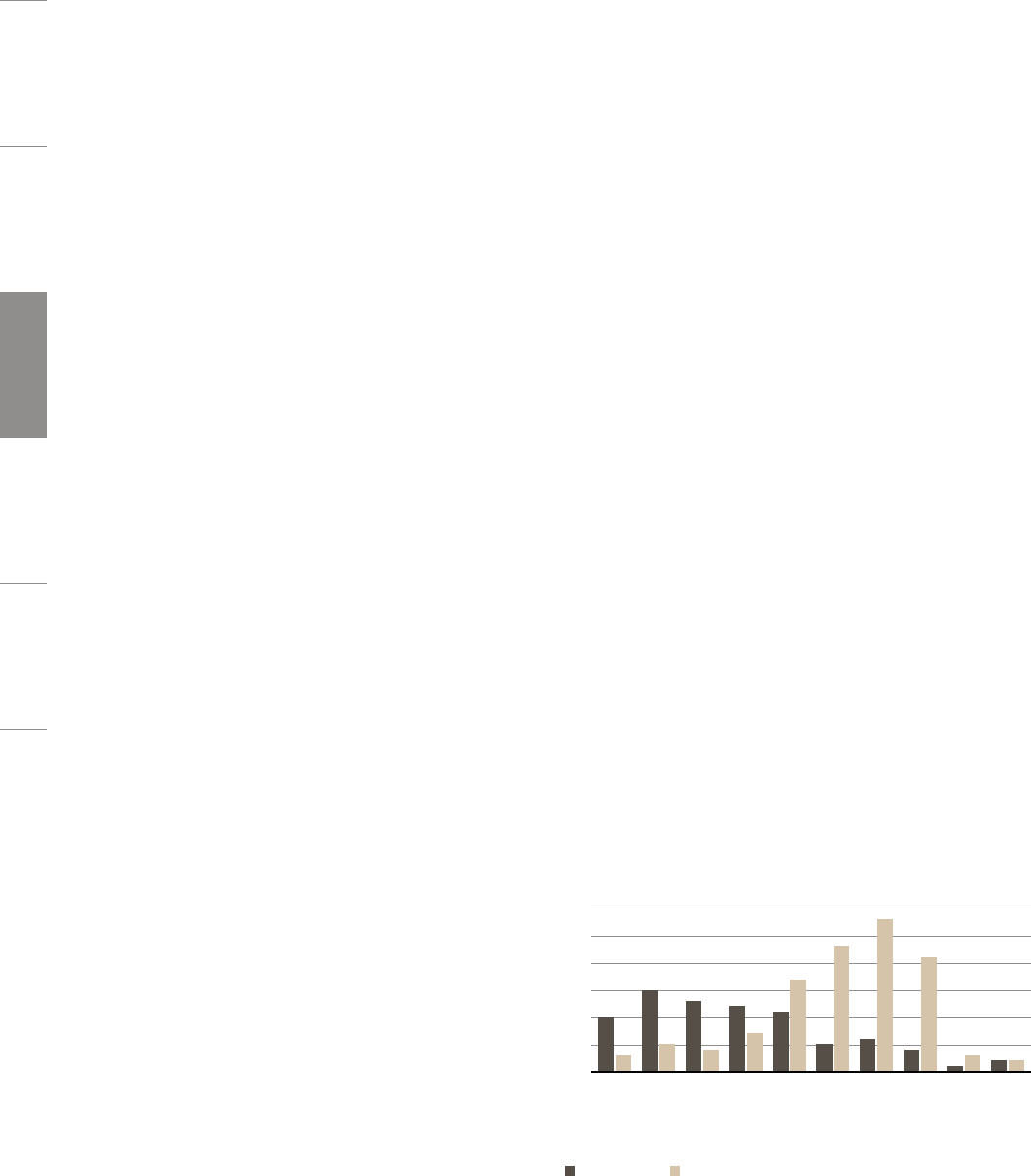

Rent decreases still moderate

In extremely tight housing markets, asking rents

(rents for new and renewed leases) tend to

respond very quickly to changes in the vacancy

rate. Rents tend to skyrocket if vacancy rates in

a region drop to around 0.5%.

This happened from 1985 to 1991, when the

nationwide vacancy rate dropped below this

threshold, and asking rents shot up 50% aer

adjusting for ination. In the current real estate

cycle, only the Lake Geneva region has such a

tight housing market. Here, rents increased 5%

annually between 2002 and 2015 – double the

rate in the rest of Switzerland.

If vacancies go up in such tight markets, rents

tend to collapse quickly. For example, rents in

the Lake Geneva region have already shed 9%

since 2015, even though the current vacancy

rate for rental apartments, 0.8%, is only one-

third of the Swiss average. Average advertised

rents have only dropped moderately nationwide.

No longer

at any price

Matthias Holzhey and Elias Hafner

Apartment buildings

140

180

80

100

160

120

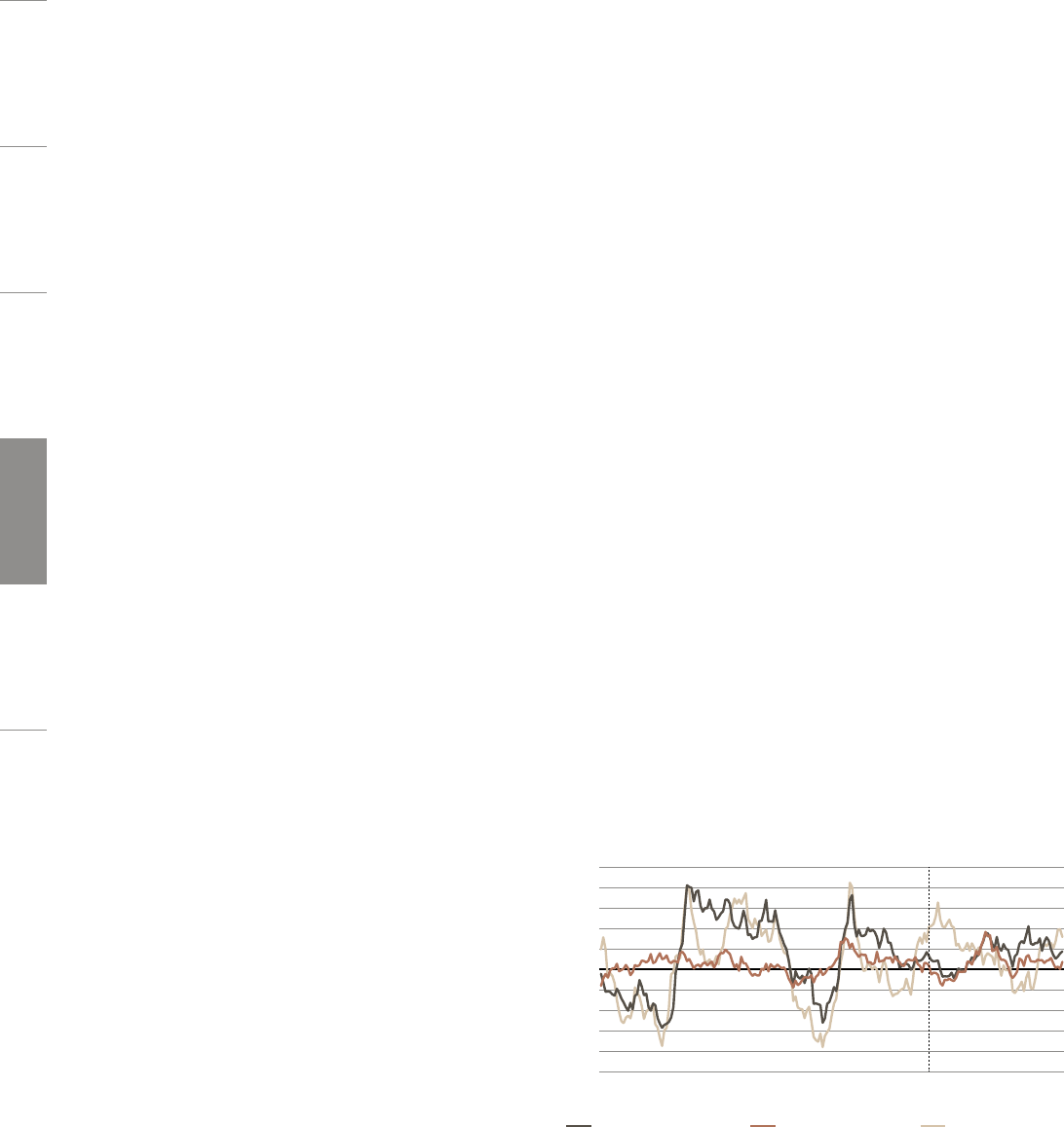

Period with rapid increase in vacancy rate

Asking rents/income

Period with rapid decrease in vacancy rate

200519851975 20151995

Corr

ection

potential

Existing rents/income

Correction potential for asking rents

Source: FSO, Wüest Partner, UBS

Ratio of asking and existing rents to income (index 2000 =100)

Global Listed Commercial Residential Mobility

17

UBS Real Estate Focus 2018

The index for asking rents is almost 3% below

its mid-2015 peak. Rents declined sporadically

in most cities and metropolitan areas, and even

in large parts of the periphery. In fact, Western

Switzerland (without the Lake Geneva region)

even showed a 1% increase last year.

Loss aversion puts o market shakeout

Psychological factors are probably responsible

for the lack of movement in asking rents, even

in municipalities with rapidly rising vacancy

rates. Loss aversion – the tendency to avoid

losses – has been thoroughly researched in

empirical studies. For many investors, a nancial

loss has up to twice the psychological impact as

an equivalent gain.

In the real estate market, loss aversion explains

why market liquidity declines rapidly when

home prices fall. Potential sellers tend to hold

on to their properties when the current market

price is lower than what they originally paid.

Loss aversion is also the reason why landlords

are hesitant to lower asking rents even aer a

prolonged vacancy. A lower rent is a certain loss

or, at the very least, less than they originally

expected to earn, which they perceive as a loss.

It may pay to wait with new apartments

When advertised apartments remain vacant for

weeks, landlords have to weigh the risk of pro-

longed vacancies against the lower income asso-

ciated with a rent reduction. If rents or rent

expectations no longer reect market conditions

by the time the apartment comes onto the mar-

ket, the asking rent will oen have to be

reduced more than 10% before tenants are will-

ing to sign a lease.

With new buildings, reductions this large can

signicantly lower yields, since the lower rents

usually have to be passed on to all the tenants in

the building. In that case, landlords may prefer

to wait for a deeper-pocketed tenant. It is no

wonder, then, that the vacancy rate has shot up

particularly quickly in new buildings, where

roughly one-ninth of the apartments are empty.

Instead of lowering rents, more landlords are

now trying to lure in tenants with incentives,

which may pose more disadvantages than

advantages.

Action recommended with existing

properties

With existing properties, however, landlords can

usually contain the income loss to one apart-

ment. Here, it pays to quickly adapt rents to the

new reality, especially in regions where the leas-

ing risk is still rising. Also, it is cheaper in the

long run to renovate apartments that no longer

meet market quality standards than to drastically

reduce the rent.

Incentives can attract

the wrong tenants

More rental apartments have been advertised

with sign-up incentives in the past two years –

from rent-free periods to graduated rental leases

to gi cards and free moves. Landlords have

turned to incentives for obvious reasons: they

get prospective tenants’ attention and avoid the

need to lower eective rents, which would

reduce property values. The sweeteners have

become almost de rigeur for commercial proper-

ties, which are rented out under long-term

leases. But it’s not clear that incentives are eec-

tive for rental apartments. Gi cards or even free

moves will likely have very little impact on a pro-

spective tenant’s housing budget and willingness

to pay more in rent.

In fact, sign-up incentives could have unintended

and undesirable consequences. They could give

the impression that something is wrong with the

apartment or landlord and thereby damage a

development’s image. They might also attract

the wrong kinds of tenants. The shorter the

tenant’s intended stay, the more valuable a tem-

porary discount or cash incentive will be. People

who are eager to live in an apartment for rent-

free months will probably move out again aer a

short period of time.

18 UBS Real Estate Focus 2018

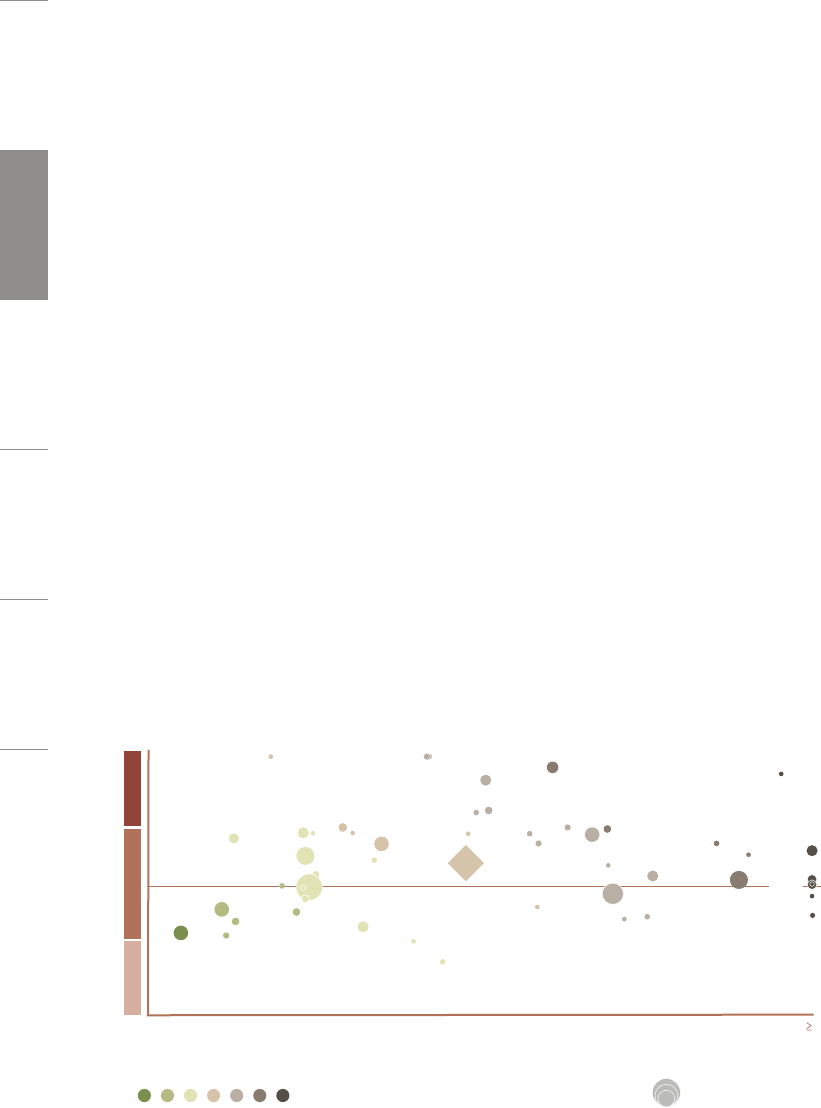

Zürich

Glattal-

Furttal

Limmattal

Zimmerberg

Zürcher Oberland

Winterthur

Zürcher Unterland

Bern

Biel/Bienne

Oberaargau

Thun

Luzern

Sursee-Seetal

ZG

La Sarine

Olten

Solothurn

Basel-Stadt

Oberes Baselbiet

St.Gallen

Wil

Aarau

Brugg-Zurzach

Baden

Thurtal

Lugano

Lausanne

Morges

Sion

GE

JU

BE

LU

SZ

FR

SO

BL

SH

SG

GR

AG

TG

TI

VD

VS

NE

1

2

3

4

5

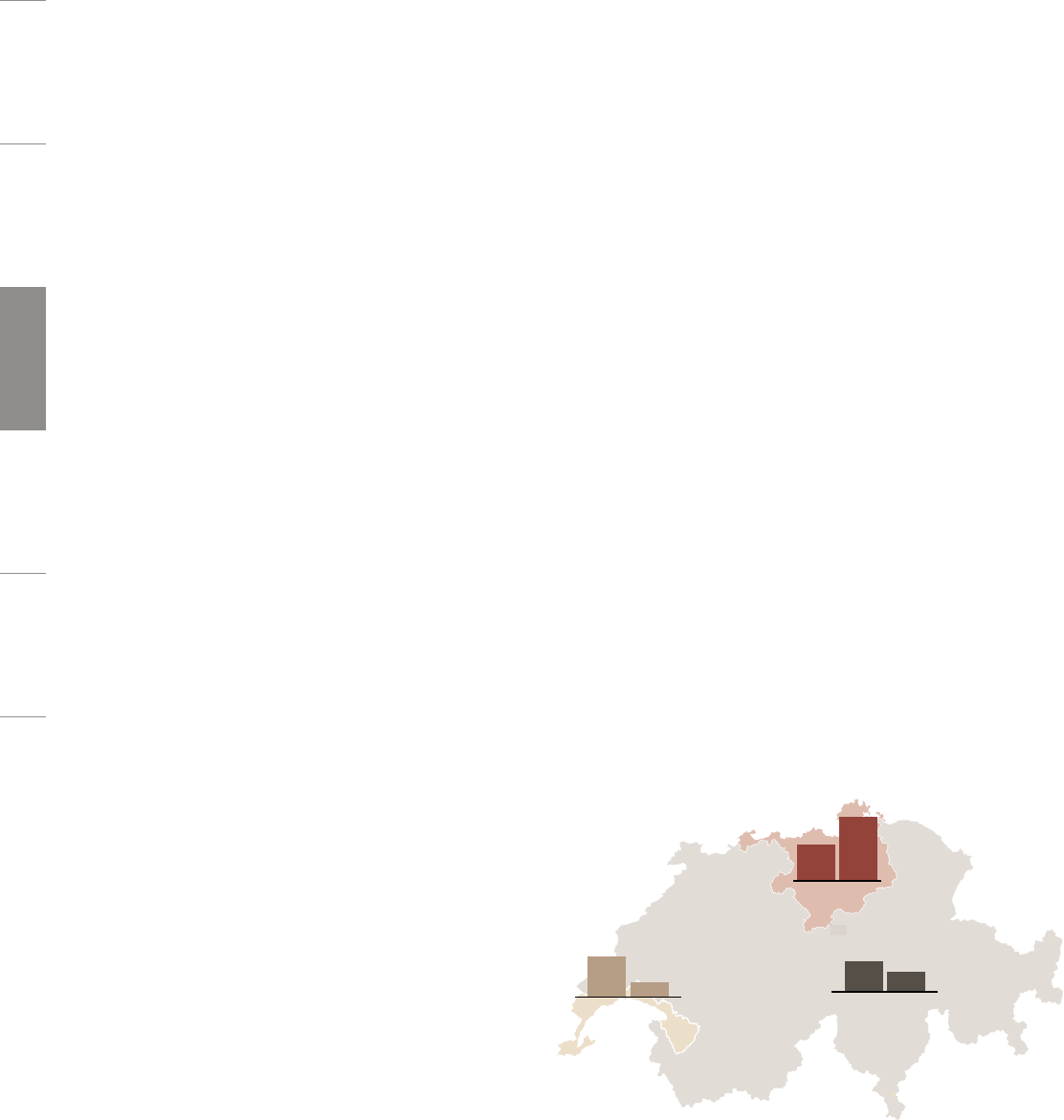

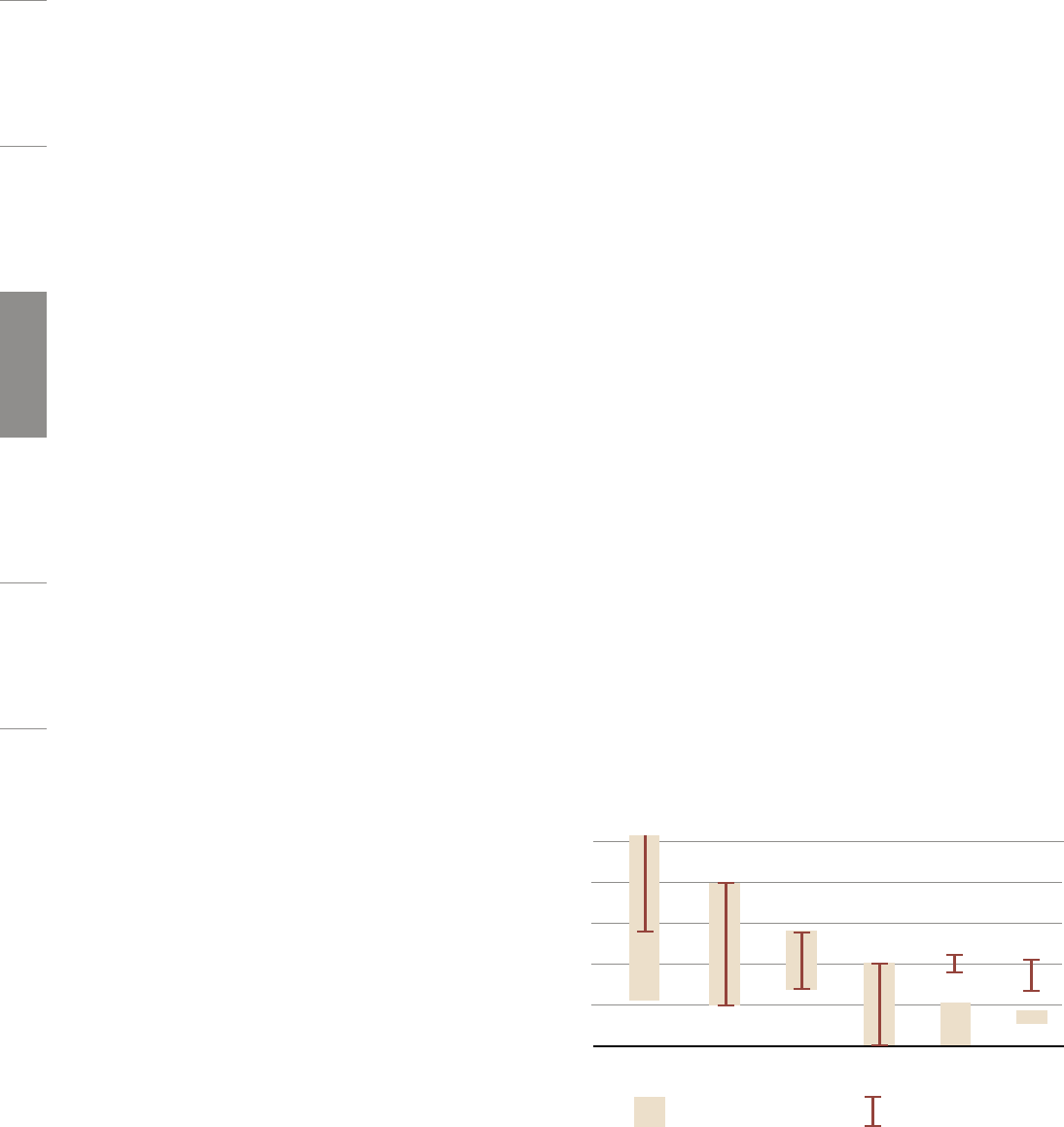

Vacancy rate for rental apartments

HighLow

Leasing risk

0

Absorption risk

Pfannenstiel

Population size

1

Vacancy rate for rental apartments based on UBS estimates of rental housing stock

2

The absorption risk compares growth in the housing stock (supply) with population growth (potential demand) and indicates whether too much

or too little is being built on a regional basis. The increase in supply is determined from the number of building permits req

uested and issued in the last

five to six quarters. Potential growth is estimated based on the past three years of population growth.

Sour

ce: FSO, Docu Media, UBS

Vacancy rate for rental apartments¹ (2017) and absorption risk² (4Q 2017) by canton (abbreviation) or population

mobility r

egion, in %

Vevey

ZH

Unteres Baselbiet

CH

LowMedium High

Rents declining at an accelerating pace

Persistently high vacancy rates put pressure on

rents. We expect asking rents to correct around

2.5% this year. But that does not necessarily

mean the correction phase is over. Unless con-

struction activity changes direction or immigra-

tion surges again, asking rates will probably be

at least 10% lower in 2020 than in 2015.

Existing rents have developed steadily over the

long term. In Switzerland, they have kept step

with wages since 1982, increasing 0.5% a year

in real terms. Therefore, current rents are not

excessive, so we don’t anticipate a broad correc-

tion in the years to come. However, asking rents

are still 20% higher on average than current

rents. This dierence will shrink when asking

rents correct as anticipated. Once this happens,

landlords will be less likely to increase rents for

incoming tenants in existing properties. They will

also have less latitude to change the terms of

existing leases if the reference interest rate rises,

since asking rents act as a ceiling for existing

contracts.

Excess supply risks in Ticino and Western Switzerland

Vacancy rates in the business centers are low

and will probably not rise much in the next

several quarters. Structural vacancy has driven

up leasing risks in the Central Plateau region

and many peripheral regions. The cantons of

Solothurn and Valais, for example, have the

highest percentage of vacant rental apartments

at around 6%, while nearly 4.5% of all rental

apartments are empty in Aargau. The trend is

extremely negative in Ticino, too. An increase

inthe number of building permits and a sudden

drop-o of immigration from Italy will likely

prompt a steep rise in the number of vacant

rental apartments by mid-year. Excess supply

risks have also risen signicantly in the Western

Swiss cantons of Fribourg, Jura and Neuchâtel,

as well as in the hinterlands of Vaud.

Global Listed Commercial Residential Mobility

19

UBS Real Estate Focus 2018

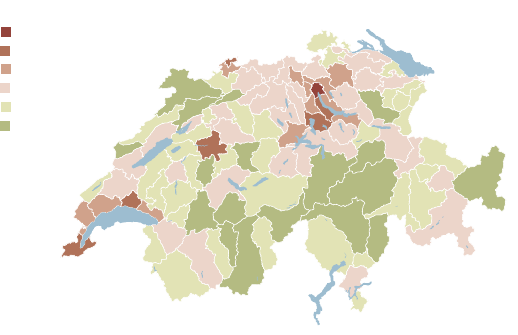

Investment outlook

Valuations peaking

Falling capitalization rates have fueled the rally

in residential investment property prices over the

past 10 years. Prices for apartment buildings

throughout Switzerland have risen nearly 60%

since 2007. Rents, however, have only risen

around 15% over the same period. As a result,

net initial yields have declined from just under

5% to 3.5%. Yields vary regionally as well, from

less than 2% (Zurich District 1) to over 5%

(Goms).

Many investors still nd these yields attractive

given the negative yields on Swiss government

bonds with maturities of up to 10 years or more.

However, interest rates should rise slightly over

the next 12 months as central banks worldwide

tighten the monetary reins. With vacancies on

the rise and rents on the decline, capitalization

rates will likely not fall any more in 2018. In

short, prices for residential investment property

appear to have peaked. Investors have largely

given up on further capital gains. This can be

seen in the stock market: the prices of residen-

tial real estate funds underwent a signicant

correction in the second half of 2017. Expecta-

tions of further increases in residential invest-

ment property prices have zzled out.

Value adjustment looms

Future investment performance depends heavily

on the long-term interest rate trends. Interest

rates will start trending upward once central

banks stop depressing them articially. A small

increase in the yield curve of 0.5 percentage

points or less shouldn’t squeeze prices for

apartment buildings across the board, however.

Investors would still be hard-pressed to nd bet-

ter places to put their money. An increase in the

yield on 10-year Swiss government bonds to,

say, 2%, however, would require substantial

write-downs. Property values would correct

around 20%. Properties in prime locations,

which have responded more strongly to falling

interest rates in recent years, could shed up to

30% of their value. Peripheral locations, by con-

trast, are less sensitive to interest rate uctua-

tions. Instead, they face a higher risk of lost

income in today’s market due to higher vacancy

rates or lower rents. We believe the most attrac-

tive locations are metropolitan area locations

situated at commuting distance from central

business districts; they oer net initial yields of

just over 3% with only moderate vacancy risks.

Source: UBS estimates

* Net yield aer all costs ar

e deducted (including maintenance) in % of purchase price

One franc of rent is worth twice as much

in Zurich as in the mountains

Initial net returns* by population mobility region, in %

under 2.5

2.5 to 3.0

3.0 to 3.5

3.5 to 4.0

4.0 to 4.5

over 4.5

20 UBS Real Estate Focus 2018

Insurers and pension funds now have greater incentives to

oer mortgages. Banks are likely to lose market share due to

stricter banking regulation. Institutional investors can choose

from several mortgage investment options.

Last year, the Swiss mortgage market broke

through the CHF 1 trillion barrier. Banks hold

roughly 95% of the total mortgage volume,

with insurers and pension funds making up only

a small portion of the market. However, the

trend appears to be changing. Insurers’ mort-

gage positions grew by around 6% a year in

2015 and 2016, while pension funds’ mortgage

books expanded 5% in 2016 aer years of

decline. Banks, in contrast, have experienced

slower growth. In fact, large banks’ mortgage

books have recently shrunk. Initial 2017 data

indicates that insurers’ mortgage portfolios are

continuing to grow faster than those of banks.

Institutional investors with a long-term

horizon

Banks nance most mortgage loans with debt

that is callable at short notice. For banks, xed-

rate mortgages are traditional interest opera-

tions: they collect the mortgage interest with

one hand, and pay depositors interest on their

deposits with the other.

Insurers and pension funds, by contrast, invest

capital that insured individuals or plan members

pay in to cover future losses or pension commit-

ments. Pension fund obligations usually have

terms of 10–15 years. For this reason, insurers

and pension funds prefer to extend long-run-

ning loans, oering 15 years by default but

going up to 25 years in some cases. They also

tend to be more conservative about loan-to-

value ratios and market segment risk. So not

only are market shares unequal, but the market

itself is segmented too.

Incentives shi due to regulation and

low interest rates

There are three main reasons behind institu-

tional investors’ current push into the mortgage

market:

Regulation

Stricter capital and liquidity requirements since

the nancial crisis under Basel III have made

nancing more expensive for banks. At the

same time, the Swiss National Bank’s countercy-

clical capital buer and stricter self-regulation

have made mortgage lending more expensive

or difcult for banks. The regulation of mort-

gage lending for institutional investors, by con-

trast, is not quite as stringent.

More money from

institutional investors

Elias Hafner

Mortgages as an asset class

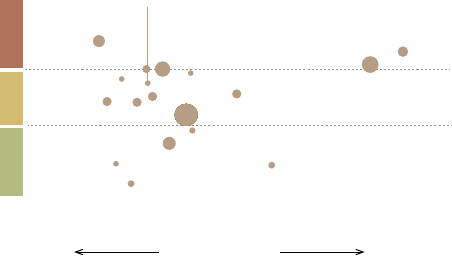

Institutional investors have a small portion

Source: FSO, FINMA, SNB, UBS

Swiss mortgage market, broken down by lender as of the end of 2008 and

2016, in %

34%

2016

2008

Cantonal banks

Large banks

Raiffeisen banks

Other banks

Insurance companies

Pension funds

34

26

17

18

4

1

32

32

14

17

4

2

Global Listed Commercial Residential Mobility

21

UBS Real Estate Focus 2018

Negative interest rates

The January 2015, introduction of negative

interest rates shied the incentives for granting

mortgages in favor of institutional investors in

two ways. First, banks do not charge most of

their private clients negative interest, so their

earnings situation is at risk of worsening consid-

erably. To prevent margin erosion in the mort-

gage business, banks have raised lending mar-

gins: mortgage rates at banks have barely

budged downward despite a signicant

decrease in the general interest rate level. Many

pension funds, on the other hand, are aected

by negative interest rates. According to Swiss-

canto’s Pension Funds Study 2017, 58% of

pension funds pay negative interest or deposit

charges, encouraging them to shi some

xed-income or money market positions to

mortgages.

Property values

The low interest environment has prompted

institutional investors to move large amounts of

capital to investment properties. Pension funds,

for example, reduced their bond positions to

32% of their portfolios in 2016 from 38% in

Independently, with a partner or indirectly

Pension funds and insurers wanting to invest in

the mortgage market have several options.

Independent mortgage lending

One option is for pension funds and insurers to

lend mortgages themselves, enabling them to

capture all the returns along the value chain.

Asof mid-December 2017, relatively large insti-

tutional investors oered 10-year mortgages

based on reference rates of around 1.3%

(banks: 1.5%). Whether or not independent

lending makes sense depends heavily on the

maintenance costs for the necessary infrastruc-

ture. As a rule, the bigger the mortgage book

and the longer its intended operating life, the

easier it will be to absorb high initial and xed

costs.

Collaboration with a mortgage partner

Institutional investors can also transfer part of

the value chain to a partner. Working with bro-

ker platforms, for example, gives them quick

access to new clients. Pension funds or insurers

can also act solely as investors. In this case, the

mortgage partner – for example, a bank – han-

dles all the administration. The return for the

institutional investor depends on the maturity;

at the moment, it should range from nearly

0.5–1.0% in most cases. Mortgage partners, by

contrast, can earn an additional return without

having to carry the mortgages on their books.

Separating the underwriting and lending opera-

tions requires properly adjusted incentives,

though. For example, the mortgage partner can

always carry part of each mortgage on its bal-

ance sheet, or the underwriter can analyze a

mortgage without knowing whether the institu-

tional investor or the mortgage partner will be

bearing the default risk and carrying the invest-

ment on their balance sheet.

Indirect investments

Finally, investments can also be made indirectly

through investment foundations or mortgage

funds. Several large banks have created invest-

ment vehicles for this purpose since late 2016

and, in some cases, have moved mortgages

from their own balance sheet into them. This

solution oers the prospect of broad diversica-

tion and the rapid build-up of a mortgage posi-

tion. Also, investors can redeem shares if they

wish. Return expectations vary depending on

the mortgage fund, mainly because of average

maturities (less than one year to six years), but

currently range around 0.2–0.5%. Rigorous

mortgage selection criteria are designed to pre-

vent these investment vehicles from only receiv-

ing “bad” loans. Unlike direct mortgage invest-

ments, these positions have to be marked to

market, which can lead to unwanted coverage

ratio uctuations when interest rates change.

22 UBS Real Estate Focus 2018

2007, and increased the real estate share to

nearly 23% from 17% during the same period.

Demand for investment properties among insti-

tutional investors remains robust, but investors

seem more cautious now. This has brought

mortgages – which, at conservative loan-to-

value ratios, act more like bonds than real

estate investments – onto the radar.

Banks still dominant, but segmentation

stronger

The spread between mortgages and xed-in-

come investments seems highly attractive at

rst sight, and not just because of the negative

interest rate environment. Mortgages have cer-

tain appealing characteristics as well. They are

an illiquid asset class, so investors demand to be

compensated accordingly. Institutional investors,

with their long-term investment horizon, can

bear the liquidity risk and collect the illiquidity

premium. Also, over the long term, mortgages

can provide diversication and carry a default

risk as low as that of bonds. Default rates can

spike, however, as the subprime crisis illus-

trated. Knowing this, institutional investors

should not relax their traditionally conservative

mortgage lending policies just to collect a few

extra basis points. These investors are also wary

of mortgage holdings that shorten capital com-

mitment periods, since they want to avoid

asset-liability mismatching.

While the market distortions caused by negative

interest rates are unlikely to persist over the

medium term, the “regulation gap” between

banks and institutional investors – due to

BaselIV, among other things – could certainly

widen even more. As a result, banks are being

forced to give up some mortgage business and

focus more on the service-oriented, less inter-

est-rate-sensitive links in the lending value

chain. At the end of 2016, insurers were poten-

tially able to invest an additional CHF 37 billion

in mortgages (estimated, not including over-col-

lateralization). Pension funds are generally per-

mitted to invest 50% of their total assets in

Swiss mortgage securities. Even if they did

choose to allocate such an unrealistically high

share of the CHF 800 billion of capital held in

second pillar plans to this asset class, they

would still make up less than half of the total

market. Clearly, banks will continue to domi-

nate the Swiss mortgage market. The market

should continue to split up into segments, how-

ever, which will ultimately lead to more robust

mortgage lending as mortgage asset maturities

become more aligned with investors’ liability

maturities.

Global Listed Commercial Residential Mobility

“The segmentation

should continue

toincrease, which

will lead to more

robust mortgage

lending as mort-

gage asset maturi-

ties adapt to

investors’ liability

maturities.”

23

UBS Real Estate Focus 2018

Crowdfunded investments in the Swiss residential real estate

market have been delivering blockbuster returns through high

gearing and compromises in macro locations. Investors have been

reaping the rewards during this fair-weather period. Concentra-

tion risks loom, however, particularly for small investors.

Too good to be true? Earn 7% a year in an

ostensibly secure asset class while interest rates

are low. Real estate crowdfunding platforms are

making exactly that promise. These platforms,

which rst appeared in Switzerland in 2015,

have brokered over CHF 200 million in invest-

ments in apartment buildings. Most of the time,

the platforms have kept their promise. Buy-to-let

and residential real estate funds are traditional

alternatives to crowdfunding, but currently oer

much lower returns: 4–5% and 2–3%, respec-

tively.

Up-close look at the dierences in returns

The large dierences in returns on equity, espe-

cially between crowdfunded investments and

residential real estate funds, are largely attribut-

able to leverage, dierences in gross rental

returns and the costs of managing the real

estate portfolio.

Gross rental return – funds oer better location,

liquidity and diversication

On average, crowdfunding providers promise

net rental incomes of nearly 4.5% of the real

estate purchase price. The portfolios of residen-

tial real estate funds, by contrast, pay an aver-

age of 3.5–4% of the fund assets’ fair value. So

why do listed funds return less?

First, they come with certain advantages, like

better diversication and greater liquidity than

individual investments in apartment buildings.

Investors are willing to pay a premium for these

advantages, lowering returns. In investment

crowdfunding, by contrast, the risk is concen-

trated in a few apartments; the secondary mar-

ket is still untested.

Second, fund properties tend to have better

macro locations. Only some 25% of the Swiss

population lives in communities with a higher

macro ranking than a fund portfolio’s median

property. Median properties in crowdfunded

ventures, by contrast, tend to rank much lower;

a bit more than 60% of the population lives in

communities with a better rating.

Third, funds always factor in a rent default rate

of around 4%.

1

That is much higher than the

average vacancy rate of rental apartments in

invested communities, which is less than 2% on

a portfolio-weighted basis. Crowdfunding g-

ures only include a vacancy buer of around

1.5% – despite signicantly worse macro loca-

tions and community vacancy rates in excess of

5%.

Higher returns

with higher risk

Elias Hafner and Maciej Skoczek

Investment crowdfunding

1

The rent default rate corresponds to the reduction in income

attributable to vacancies and uncollected rent relative to net

target rent.

What is investment

crowdfunding?

Investment crowdfunding – also known as equity

crowdfunding or crowd investing – in real estate

enables many investors, each using relatively little

capital, to purchase apartment buildings through an

online platform. That way, even small investors can

co-own a residential investment property and prot

from rental income and rising property values.

24 UBS Real Estate Focus 2018

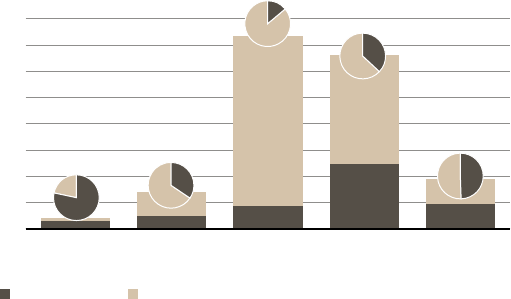

30

0

10

40

20

ExcellentAverage Very poor

Investment crowdfunding

Crowdfunded properties oen found

at average locations

Sour

ce: FSO, various investment crowdfunding platforms, annual reports of various real estate funds,

Wü

est Partner, UBS

Percentage of properties, broken down by investment vehicle and

distribution of multifamily housing inventory and by macrolocation category

(in % of the total inventory)

Macrolocation of municipality

Real estate funds

Inventory of multifamily dwellings

in Switzerland

Finally, rental incomes from crowdfunded invest-

ments are assumed values. The rents for apart-

ments with published square-meter prices tend

to correspond to Wüest Partner’s asking rents in

upmarket properties in the same community.

This is an optimistic assumption at best, given

the micro locations of crowdfunded properties.

These factors provide a broader context for inter-

preting the dierence in gross rental returns.

Real estate platforms do not appear to be buy-

ing at an especially favorable price-to-risk ratio.

Managing real estate portfolios – funds are

not cheap

Managing a real estate portfolio incurs expenses:

for taxes, maintenance, repairs and administra-

tion.

Crowdfunded portfolios set aside around 5%

ofrental income for maintenance and repairs.

That may be realistic in the short run for most

new or newly renovated properties, but is prob-

ably too low in the long run. Residential real

estate funds, by contrast, put the eective costs

at 10–15%.

Crowdfunding platforms charge around 10% on

average for portfolio administration. With real

estate funds, the fund management company

and custodian bank (including external advisors

and administrators) collect 15–20% of total rent

income.

Taxation is also dierent. End investors have to

pay tax on income and capital gains from

crowdfunded investments. Real estate funds are

taxed separately, as well. The actual rate varies

considerably, depending on the regional focus

and investment type (direct or indirect), but

tends to average close to 15%.

To recap: crowdfunded investments incur aver-

age costs of 15–20% of rental income before

personal tax, compared to over 40% for residen-

tial real estate funds. The resulting return on

invested capital is around 3.5% for crowd-

funded real estate and around 2% for residen-

tial real estate funds. However, crowdfunded

investments make ambitious assumptions about

maintenance and repair costs, which will proba-

bly rise over the long term. Also, end investors

have to pay taxes on a larger slice of their

returns from platforms than from funds, since

about half the funds hold the real estate directly,

making distributions to end investors tax-ex-

empt. Crowdfunding investors also have to pay

extra fees, including property gains taxes, if the

property changes hands. On balance, it remains

to be seen whether crowd investing is in fact

more cost-efcient.

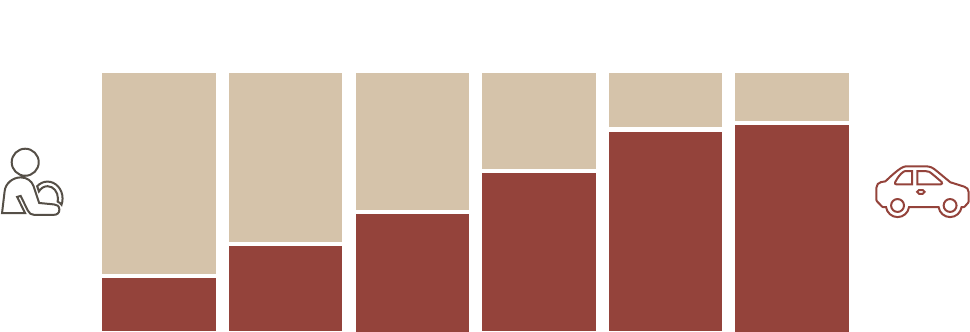

Leverage – the most important performance

driver

Leverage is very attractive given the historically

low mortgage rates available today. Crowdfund-

ing platforms and residential real estate funds

are taking out long-term mortgages with rates

at generally less than 1%. Mortgages on crowd-

funded properties usually average 60% of the

property value, while funds have a debt ratio of

around 20%. As a result, the return on equity

for crowdfunded real estate is 6–7%, compared

to only 2.5% for residential real estate funds.

Global Listed Commercial Residential Mobility

25

UBS Real Estate Focus 2018

Residential property – investment forms at a glance

Buy-to-let Investment crowdfunding Residential real estate funds

Minimum investment Several CHF 100,000s Generally CHF 100,000 Less than CHF 100

Gross rental return* Nearly 3.5% 4 to 5% 3.5 to 4%

Return on equity 4 to 5% (before deducting

administration costs

assuming a 60% LTV)

6 to 7% (aer deducting

administration costs)

2 to 3% (aer deducting

administration costs)

Gearing Up to 80% 55 to 65% Around 20%

Financing costs Variable Generally less than 1% Generally less than 1%

Taxes Rental income counts as taxable

income aer deducting nancing

and maintenance costs. Selling the

property triggers additional taxes

such as property gains taxes.

Distributions count as taxable

income. Selling the property

triggers additional taxes such as

property gains taxes.

Fund charges and taxes oen account

for 10 to 20% of net rental income.

Income tax must be paid on distribu-

tions from funds that hold indirect

real estate investments. No income or

capital taxes for funds that hold direct

real estate investments.

Administration costs

(as a % of net rental

income)

Property management incurs

additional costs if the work is

outsourced.

Approx. 10% (including

performance fee upon reaching

a minimum occupancy rate)

15 to 20%

Investor’s property rights

and say in decision-making

Entry in land registry,

sole ownership

Entry in land registry, co-ownership

(25 owners on average)

No entry in land registry, no say in

decision-making

Typical property size CHF 0.5 to 1.2 million Median property CHF 4.5 million Median property CHF 7.8 million

Diversication None Low Medium to high

Liquidity Illiquid Poor Relatively high

*

Net rental income divided by purchase price/market value (aer deducting vacancy [buer])

Source: UBS, as of 15 November 2017

Only for risk-tolerant, broadly diversied

investors

Risk, in other words, is a big reason for the dif-

ferences in return on equity. We believe the mar-

ket cycle for apartment buildings has reached an

advanced stage. Given the high gearing of

crowdfunded investments, relatively small inter-

est rate hikes or declines in rents could trigger

signicant corrections. If market realities do not

live up to optimistic expectations for high rental

incomes, low vacancy rates at average locations

or minimal renovation requirements over the

investment period, the annual aer-tax return

will drop – and with it, the buer for corrections.

If vacancy rates and maintenance and repair

costs turn out to be typical for the market, the

investment will likely turn a loss if the property

value experiences a 10–15% correction over an

average investment horizon of six years, and so

will underperform an investment in residential

real estate funds. If property values decline 10%

with a loan-to-value ratio of 60%, investors will

lose a quarter of their invested capital (excluding

rental income). Many small investors, in other

words, will bear a high concentration risk if they

allocate a large portion of their total assets to

crowdfunded investments, regardless of shared

ownership of the property.

Investors able to absorb signicant losses in a

single position – say, because they have a large,

broadly diversied portfolio – may nd crowd-

funding a welcome opportunity to boost returns

by making highly leveraged investments in apart-

ment buildings at peripheral macro locations.

Club deals are another alternative, where several

wealthy investors put funds into real estate with-

out going through platforms.

26 UBS Real Estate Focus 2018

Global Listed Commercial Residential Mobility

Sales per square meter are highest in the largest train stations

due to robust demand. Shopping centers in quieter locations

are, however, feeling greater pressure. Malls are looking for

new ways to boost visitor numbers. Leisure and entertainment

oases are gaining stature.

Shopping malls in train stations have the highest

sales per square meter on an annual basis. In

2016 (latest available data), retailers at Bern sta-

tion generated around CHF 31,000 per square

meter, followed closely by Lucerne station,

Geneva Cornavin and Zurich Central Station

with around CHF 25,000 per square meter. By

comparison, the Glatt shopping center, which

topped the list of Swiss malls without a direct

station connection, generated only CHF 14,000

per square meter. The main reasons for the high

sales are the long store hours and easy access to

quick shopping for commuters.

No wonder demand for space at major public

transit nodes remains strong. Vacancies are rare,

and rents are high. Retail trafc should increase

over the long term too, since SBB expects com-

muter numbers at Switzerland’s biggest train

stations to increase around 50% by 2030. Inves-

tors have responded by building new retail space

near train stations – including the large malls

“Europaallee” and “Welle 7,” which recently

opened next to Switzerland’s busiest train sta-

tions in Zurich and Bern. Retail space has been

added at other train stations too, including

Bellinzona and Zurich Oerlikon.

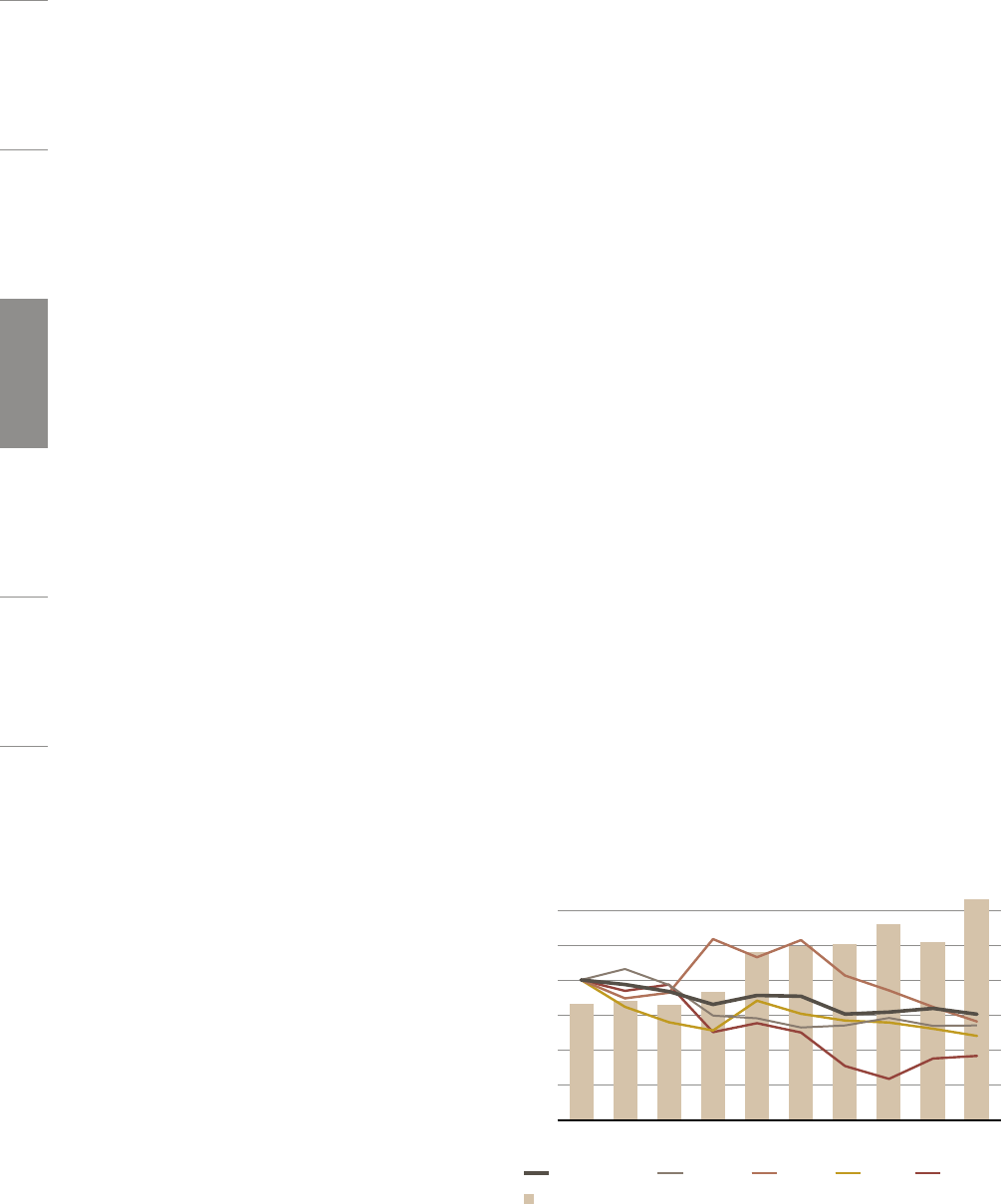

Conversion edges out new construction

Shopping centers in quieter locations are strug-

gling with plummeting sales in absolute and

per-meter terms. In 2016, they sold over 10% or

CHF 1,000 less per square meter than in 2010.

Investor sentiment has slumped as well: while

over 60 new malls opened between 2000 and

2009, only 18 are expected to open between

2010 and 2019. Last year saw only one new

opening, but it was a signicant one. The “Mall

of Switzerland” in Ebikon boasts close to 50,000

square meters of retail space, and ranked num-

ber four by size nationwide at its opening in

November – or number two if leisure and enter-

tainment space are included. Other new malls,

“Mattenhof Süd” in Lucerne and “The Circle”

at Zurich Airport, are planned for opening in

2019.

Market saturation, the growth of e-commerce

and widespread shopping tourism have

prompted investors to try a dierent approach

to improve their chances of success: renovation.

The number of conversion and rehabilitation

projects increased rapidly between 2008 and

2015. During this period, almost half of Switzer-

land’s malls underwent a complete or partial

makeover. Owners clearly hope that moderniz-

ing and sprucing up their retail space will attract

Shopping malls

reinvent themselves

Maciej Skoczek and Sandra Wiedmer

Retail space

25

15

30

0

5

20

10

2000/01

2002/03

2004/05

2006/07

2008/09

2010/11

2012/13

2014/15

2016/17

2018/19

Investment activity on the decline

Source: GfK, UBS

Number of new and remodeled shopping centers

New

Remodeled

27

UBS Real Estate Focus 2018

Waldhotel at Bürgenstock Resort Lake Lucerne, Obbürgen (Stansstad)

more visitors and boost retail sales, thereby

increasing demand for space and raising rents.

Renovation activity has, however, weakened

since 2016 – not surprising since around 90% of

Swiss malls were rebuilt or renovated between

2000 and 2015.

E-commerce hampers brick-and-mortar

competitors

The classic mall concept has seen its day. Today,

investments in shopping centers will only deliver

the expected returns if the centers themselves

adapt to the new market realities. The brick-

and-mortar sector is losing revenue to shopping

tourism and online retailers. In September 2017,

retail sales had fallen more than 5% compared

to the end of 2014. A tenth of all retail sales in

Switzerland are now generated through the

internet.

E-commerce poaches most of its sales from the

brick-and-mortar non-food sector, but more

food purchases are likely to shi online as well.

The two largest online food retailers, for exam-

ple, have increased sales over 40% since 2010,

while traditional channels have seen a slight

decline in food sales. New online providers in

the food market will likely steal additional mar-

ket share from brick-and-mortar stores in the

future.

Paradigm shi to leisure and entertainment

centers

Online retailing will probably lower the demand

for space among retailers even further. To com-

bat vacancies, which could squeeze them out of

the market or shut them down altogether, many

shopping malls will have to overhaul their mix.

Existing malls are attempting to stand out from

the online retail world by oering shoppers

experiences that they cannot get in cyberspace.

The advertising slogan for the “Mall of Switzer-

land” is a prime example, “Where shopping